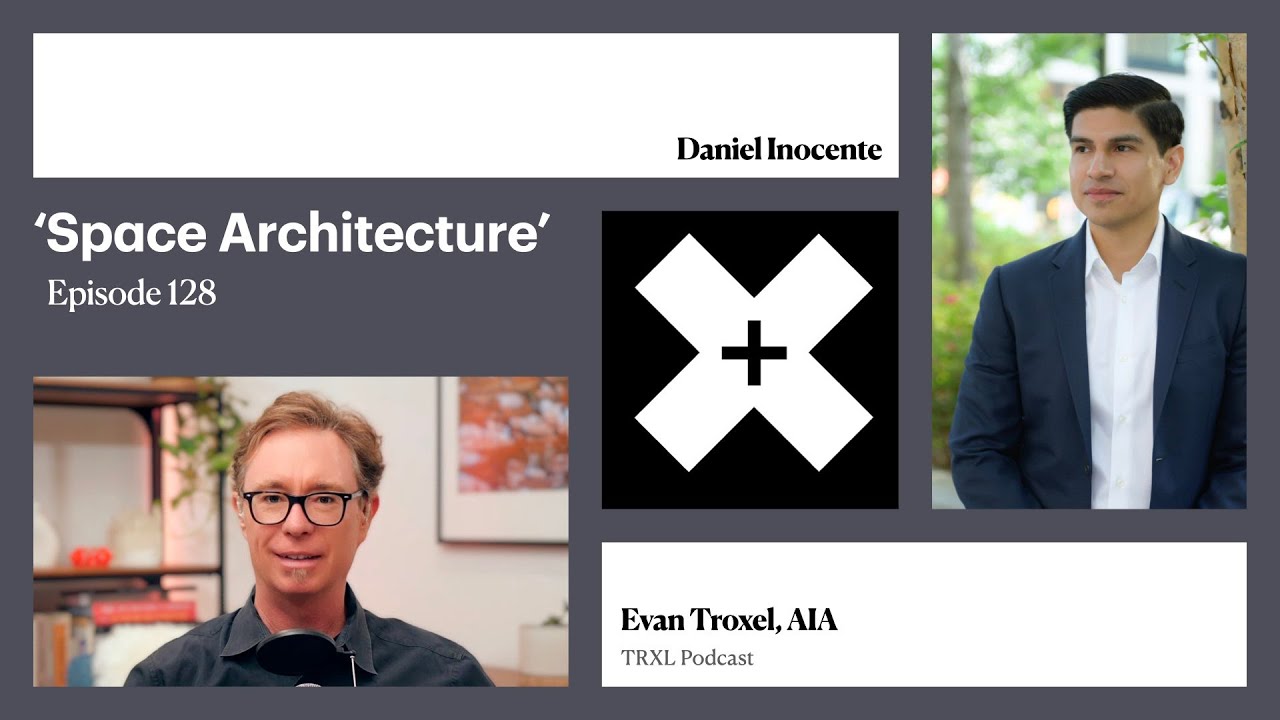

128: ‘Space Architecture’, with Daniel Inocente

A conversation with Daniel Inocente.

Daniel Inocente joins the podcast to talk about the field of space architecture. We also chat about his experience working at firms including SOM, HKS, Gehry Partners, and NASA that informed his pedagogic approach in architectural education to address the challenges in bridging the gap between practice and academia, digital tools used for design from mixed use projects to high rises to space architecture, and much more.

Episode Links:

Connect with Evan

Watch this episode on YouTube

Transcript

128: ‘Space Architecture’, with Daniel Inocente

_________

[00:00:00] welcome to the TRXL podcast. I'm Evan Troxel. This is the podcast where I have conversations with guests from the architectural community and beyond to talk about the co-evolution of architecture and technology. A little bit of housekeeping before I introduce my guest for this episode. Would you like to receive my Troxel AEC tech newsletter that I send out on a weekly basis. In it, I linked to and comment on the quickly evolving tech and AEC landscape. Each edition has a curated shortlist of things that I think are worth paying attention to so we can all be aware of how tech and AEC are evolving. I won't spam you ever. So if you'd like to get my free newsletter head over to TRXL.co and click on one of the subscribe buttons.

Okay. In this episode, I welcome Daniel Inocente. Daniel is an architect space architect adjunct professor of architecture [00:01:00] at Arizona State University, and co-founder of ATOM. He has experience working for architecture and engineering firms and government, including SOM, Gehry Partners, HKS and NASA. Daniel's expertise spans various sectors, including commercial transportation, aviation, government, culture, science, education, and residential.

He also has worked in the aerospace industry, leading partnerships with government and commercial partners. He integrates interdisciplinary and diverse ideas, leveraging his combined knowledge of architecture, technology, and space architecture. In this episode, we discussed the field of space architecture, which involves designing infrastructure and habitats for space exploration and colonization. We talk about design challenges, including optimizing volume co-locating spaces and functions. And developing sustainable communities. We also chat about the design process that involves working with experts in material science, engineering, [00:02:00] propulsion, and radiation, who and what is currently inspiring Daniel, and more. So without further ado, I bring you my conversation with Daniel Inocente.

Evan Troxel: Daniel, welcome to the podcast.

Great. Thanks for joining me today.

Daniel Inocente: Thank you for inviting me and for having me here.

Evan Troxel: All right. Well, I, I would love it if I, I know a little bit about your backstory, and it's fascinating, so I would love it if you would tell the story of your trajectory in your architectural career.

Daniel Inocente: Yeah. With pleasure. So I studied architecture. Um, I was born and raised in Los Angeles. Um, I was surrounded by a lot of very interesting activities happening in architecture, especially with, you know, the West Coast architects. Um, Frank Gehry, Thom Mayne, looking at progressive movements. Um, my interest in architecture began when I was in high school.

I really [00:03:00] wanted to dive into a field that was both creative but also technical and allowed me to bring conceptual ideas into the world, um, and concrete terms. And so architecture really inspired me to think about that. And I read a lot about the work that Frank Lloyd Wright was doing, Le Corbusier Gropius, you know, just all the modernists.

Um, and even going back through time looking at historical works. And so for me that was always inspiring. The, the challenge of how do you take an idea about settlement, about building, about construction architecture, and then bring that into the world,

um, through different lenses. And so technology has a huge role to play in that.

And I've also been fascinated by technology, thinking about, um, digital technologies and how we can start to use technology to help design better buildings, better cities. Um, and visions for the future. So that's a little bit about my background. And then eventually, [00:04:00] you know, I finished school. I got to work with Frank Gehry, uh, Gehry Partners.

Um, I got to work on some pretty exciting projects there. Very artistic, hands-on building models, designing, sketching, using three D modeling software. Um, I even got to work on his personal house at some point, a new house that he was building. Um, and so I was on site with the contractor with the builders, um, three D modeling shop, producing drawings, you know, helping them, um, build his house.

And then I also got to work overseas when I was there. So I got to work on projects in the uk, um, the batter, sea development. And that was really exciting because, you know, his design aesthetic is really out there,

which is the envelope in terms of creativity.

But to get to that creativity, you have to go through a lot of technical hurdles.

And it's not just about, you know, construction, but also how do you communicate that idea with a contractor, with a manufacturer, with a builder. And, [00:05:00] um, digital modeling had a lot of importance in that.

Um, and then eventually I got to work for NASA for a year. Um, and so that kind of rekindled, um, an interest in of mine that I've had since childhood in space.

And I can talk a little bit about that later on.

But, um, then I moved to the east coast. I worked for HKS in Washington DC for a couple years and eventually ended up in Manhattan working for SOM for five plus years. And while I was there, um, I got to work on mixed use developments, um, high rise airports, museums, um, cities, like the, you know, large scale urban planning.

Just a wide range of projects really, um, around the world. And at the same time, I was leading research efforts in space and re kind of like reigniting. This, um, interest that I had in of mind from when I was a kid and thinking about space and how we can, as the architects and designers and urban planners and engineers bring ideas [00:06:00] from the terrestrial world into the space sector.

kind of leading up to where I am now

now I work as a space architect,

Evan Troxel: Great. And, and you're, and you're teaching as well. And so you're kind of bridging the gap between academia and practice. And I mean, that's a little bit unique because there's many people teaching who are not also practicing. They might have a similar experience as you working in medium and large offices. And that has led them to teaching in design studios. But, uh, continuing to practice. A lot of people have kind of pick a place to land and, and they pick academia if they're a tenured professor, anyway, it takes up all their time, I'm sure. Um, and so you're still kind of bridging between two worlds of academics and, or I should say academia and practice.

Right? And, and as a space architect, it's still, well, you tell me. Conceptual Is it still very conceptual work or is it actually going through the process of, of building, because you [00:07:00] talked about this, the importance to you of synthesizing ideas into reality. And it seems to me like the timeframe for space architecture is, you tell me how long it is, but it's still out there, like it hasn't, hasn't hit yet.

And, and we're not building in space yet. And so, uh, I would love to hear kind of your take on all of that because of your, your

passion for both of those things. Uh, academia and space architecture at this point.

Daniel Inocente: Yeah, I think that touches on the importance of research. You know, before, I think for every architect out there or any significant work, before you get that big commission, you have to have some thinking behind

it. There has to be some research behind it, and that's what we actively do. You know, as thinkers, designers, architects, um, we we're constantly looking for ways to solve

problems.

And so that precedes the problem itself before you actually have the opportunity to, um, solve that. And for me, academia is very important. Um, I've always wanted to teach. I [00:08:00] had the opportunity to start teaching at Arizona State University. Um, it's a very different environment, an amazing campus. Um, very interdisciplinary.

They have a lot of different departments, a lot of faculty, um, experts in different fields. And I love talking to them, especially with the architecture department. They're very creative and forward-looking. And so they gave me the opportunity to teach, um, studios there around design master studios. And so these are students who are just finishing up their masters and going out into the world and they're interested in thinking about architecture through the lens of space, space architecture, through, um, thinking about digital design and other, other ways of, you know, improving the built environment.

And so what I try to teach there is, um, I try to teach a little bit of interest in technologies that are outside the domain of the building environment, you know, like the, the a e c

industry. And then help them think through ways of . How can I take some of those ideas or technologies and bring them into [00:09:00] the terrestrial world?

And so one studio I had was, I introduced students to thinking about space habitation and then understanding what are the different kind of components and technologies that go into space, habitation, the challenges. And then immediately after that I said, okay, so now how do we design a facility where you can develop those key technologies, basically like a space research center.

And those space research, research center become, you know, just like an ecosystem of, um, development where you can, you can start to produce new materials, start to test new materials, do things like 3d printing, um, do some material science. So there's a lot of different programmatic components that come into this, but I believe that if we're gonna talk about space, going to space and making it sustainable, we need to have places where we can develop this technology, develop these systems.

Um, and most of the time, . , this is happening, you know, in the domain of like government agencies where they do a lot of the testing,

but also in large [00:10:00] aerospace companies where they have facilities. Um, a handful of aerospace companies can do that. But if you can give that capability to students and to young entrepreneurs, I think you can accelerate a lot of the thinking that is, um, pushing us to go, you know, into space and think about permanent space habitation and settlements and other things like that.

Um, but yeah, I would say for, you know, for bridging the gap between research academics and practical applications of space architecture, it's definitely not easy because when you're working with, um, an environmental, an environment as hostile, as outer space or on different planetary bodies, there's so many factors that go into it.

Not to mention the cost associated with developing these key technologies or capabilities. , but there isn't, I mean, there is a lot of, I would say, support for that. Um, not just here in the US through nasa, but also [00:11:00] abroad at different space agencies. And I've had the opportunity to work with different space agencies, um, in Europe and other universities, um, around the world.

And so there's, this is a global, you know, thing that people are pursuing and it's being tackled from different vantage points. There's also competition, but that's good, that's health healthy competition is always good and there's definitely a lot of progress happening now. Um, if you, if you keep up with the news and aerospace developments, you'll see that there's a lot of interest in going back to space, to the moon, to Mars and making those technologies possible.

Um, but I always love teaching, so I'm gonna continue to teach and I will try to challenge students in different ways. Um, next semester I'm actually teaching something very different. It's a high-rise studio. So thinking about . High density urban development in Manhattan. And I have a site, so from the students, and then I have some ideas about what it means to develop high [00:12:00] density.

And then, you know, in, in a time where housing is very important, in a time where sustainability is very important and where, um, we're kind of rethinking the way that we work and live. Um, and so that's, I think, also another important topic. Maybe not, I would say not completely connected to space architecture, but that's where I come from.

You know, I, I worked in two different worlds and I'm still fascinated by the two worlds. And every once in a while I find a ways to bridge 'em. It's not always it clear and people ask, well, how do you, how do you do these two different things? You know, it's not, it's not clear to me either all the time,

you just have to connect the dots once, whenever they become visible.

yeah,

Evan Troxel: yeah. I think, you know, you said rethinking the way we work and live, and that to me is something that happens all the time in academia. There's a constant kind of questioning of why do we do it the way that we do it? And at the same time, there we are still teaching students today the same way that we've been teaching students for. Decades upon [00:13:00] decades for a profession that is slow to change, right? It's slow to adopt new business models, it's slow to adopt new technologies in much of it, not everywhere. Right? There are obviously, you know, the bell curve is real in architecture too. There's the early adopters, there's the late adopters, there's the, the whole gamut.

And so I think you're probably more on the, the earlier adopter side for sure, right? The innovator side and, uh, but, but you can't, my, my question I guess is, or maybe, maybe my, I'll, I'll provoke you and just say like, how do you square up with the academic system as is when it is really designed to pump out graduates into The existing situation that so many of them will find themselves in, which is of the past, right? Like it is very much built on the practice of old, not the practice of new. You've, I think, found a different path and [00:14:00] you can even communicate that to students and you can show them that they don't have to fit into the quote unquote, you know, project manager role or the designer role in a traditional firm, because there are

additional avenues out there.

But, but I feel like you're against the grain in a, in a system that's, that's not changing very quickly either. In addition to professional practice, neither of them are changing very quickly. You're, you're on the

bleeding edge, but, but how do you kind of square that and how, how do you approach that when you're talking to students?

Daniel Inocente: Yeah. And one thing is for sure, you're never gonna have a smooth ride when you're trying to do things like this. Like you're always gonna find friction. Um, and so it's good. Actually, resistance is good because what I've discovered is for every individual, you know, there's always like something that is innate to you.

Whatever interests you, you know, like if there's a saying that we're all unique, I think we're all genetically unique. There's something unique to you, unique to me, unique to every individual. [00:15:00] And if you can tap into what makes you different, what you're really fascinated by, and you just like master that, it becomes easy for you to do that.

You know, you work hard at what things that are easy for you. And if you can do that in architecture, you might find a niche where it's like, I'm interested in, you know, architecture through the lens of software, or make, I'm interested in architecture through the lens of economy or philosophy or sociology, whatever.

Um, and then you tap into that potential and you start to, you know, craft a different mindset. Um, it makes you different. It sets you apart. It becomes your power, you know, and that's, I think one thing I try to tell students is, um, don't try to repeat what others are doing. Definitely don't like, I'll share my, my journey with you, but don't repeat my journey.

Um, everybody has a journey to take and you have to discover that what that is. But always question in my what if I'm doing something, am I enjoying it? And if after a certain period of time you're not enjoying it, You have to find a way to like shift gears.

You know, you have to find [00:16:00] something that you're really truly enjoying because, um, the only way you could get good at something is through a lot of hard work and repetition.

And sometimes that, that becomes boring. And then you wanna shift over to something else and you, you know, you have to like, you have to really like dive deeper into something that's interesting and you can push the boundaries in that way, but it has to come natural to you.

Evan Troxel: Yeah. Yeah. The, the whole idea of of space architecture is really interesting because there's so much being learned about how to build in other places. Right. And so you talk about kind of the extreme or, uh, really harsh conditions as far as, you know, humanity would be concerned in o other locations that are On different planets. Right. Uh, it could be on the moon, could be on Mars. Uh, as, as a couple of, you know, examples that are probably, you know, readily, we can see those, we can see that happening. [00:17:00] And so when it comes to, like you talked about spec specific kind of, uh, facilities, ecosystems for developing ideas for habitation of other places like that, and there's so much being learned so quickly, how are you sharing that with students so they're not always starting from scratch when it comes to designing Or pursuing ideas for habitation on other planets. Is there like a compilation of knowledge that's being collected and and available, made available to students in that regard? Be beyond like the government agencies who tend to keep all of that stuff secret. I would assume, I mean, maybe I'm wrong, but it seems like architecture's always kind of suffered from this, where it's like everybody has to go it alone. All the students are prepared through school to approach each project a blank page, [00:18:00] which is on one way. In one way, it's very good, right? It's fresh thinking on another way. It's like you are reinventing the wheel in many cases, right? And so how do we get beyond that and how do we share, you're a bridge between space architect and student, so you could share it personally. Is it happening at a scale larger than that? So that. We don't suffer the same consequences we have here, which is everybody has to pay their dues. Everybody has to climb the same ladder. You have to suffer the same way that I did through the, the process of becoming an architect. Uh, and, and so I'm just interested if that's changing at all when it comes to space architecture or is it more of the same

Daniel Inocente: Yeah, I guess in academics so far, I've experienced a lot of like free flowing

information. You know, people are willing to share, willing to help, to connect you with, um, resources that you need. And then of course, when you get into the commercial world, [00:19:00] it's always a competition. Um, certain companies, firms have a secret sauce,

whatever that is, and they don't wanna share that with anybody because.

They're all competing for different clients, especially in the AEC industry. Um, and I've experienced, you know, a combination of that and not just in the aerospace world, um, but also in the building world. And so I sometimes see it as like, not necessary. Um, I think the more we share, the better, the faster we can

move, you know, protecting ideas, protecting IP sometimes can get in the way of progress.

but it is also a good metric for innovation, you know, like capturing new ideas, technologies, patenting, um, and then documenting that. And then, you know, just making sure that we're together collectively creating new ways of, of, um, solving our problems, um, as a society.

Um, but I do say that there is a lot of great resources for students. Um, so once you get to a certain level, [00:20:00] like once you get to the, let's just say the hardware level, Um, or even like the technical level in a building design, you're gonna come across, um, a threshold where you can't access that information unless you're on the inside.

Um, but there is enough information out there, especially with the internet now you can learn how to do a lot of great engineering. A lot of, you know, learning a lot of things about design and the building industry or aerospace. Nasa, um, our government agency, they publish a lot of work. Um, if you go to their NASA tech part, they have a roadmap, really well documented roadmap on all the different discrete technologies and capabilities that are, are needed to sustain humans in space on the moon and Mars.

And these are all areas where we can actually go and say, I have an idea for this technology. Maybe I can come up with a company to develop this technology. And so if you're inspired to do that, you know, go and check out the. The, kind of like the roadmap there. [00:21:00] Um, but then there's also publications If you go, NASA has also really great, um, websites for publications.

And these are all govern. A lot of them are government funded. They're in partnership with universities. Um, the ai, AIAA is also a really good resource for this. You can look at the publications and there's also great conferences. So one thing I tell students is go to conferences, go to networking events, go meet other people, connect.

And, um, you'll find that that's one of the best ways to, you know, just to accelerate your career, um, face-to-face interaction with other experts and professionals because anybody who's successful will not deny you. Um, you know, some help.

Evan Troxel: I say the same thing. I, the, I feel like conferences are so important for exactly that, that the best part of a conference is not the classes, it's not the keynotes, it's not the expo hall, it's the person to person interaction that you can have and making real world connections. Definitely. It goes [00:22:00] above and beyond online connections. And I, I, I don't exactly know why, because I can connect with anybody anywhere in the world. I mean, this, this, podcast is an example of, of me doing exactly that every single week talking to people all around the world, but it doesn't compare to meeting in person, right? So there's just something different about it, and you really do have to take those literal

steps to get out there and do that, and. Pay for a ticket to those conferences, even if it, you know, figure out a way to get to those conferences.

I know a lot of people who will go to, they will not attend a conference, but they will go to the place where the conference is happening because the great conversations happen outside of conference hours many times.

And they'll just meet up with people for dinner, for

coffee, for whatever, because they know that they're gonna be in a certain place at a certain time, and it's a great time to connect with people. So

I, I totally agree with you. I think that that is one of the best ways to, to get out [00:23:00] there and gain the knowledge that only people, I, well, I should just say that people will, will, are more willing to share that in person over a, a very low key conversation, a very real conversation than they are gonna be, um, pushing that stuff over email or whatever for whatever reason.

But it's just, that is actually how it works.

Daniel Inocente: Yeah, absolutely. Everybody wants to connect

and so if you can find a good motivator to connect, uh, find it some, find something that you love doing, and then go to those conferences and learn from other people.

Evan Troxel: Yeah,

Daniel Inocente: Yeah,

Evan Troxel: I, you, you strike me as the kind of person who's been really motivated to get out there and experience things and connect with people, and that seems to be the, the trajectory that you've lived in your career. I'm, I love how you follow your passion. Like you, you, you said you also tell the same thing to your students.

If you're getting bored with something, often that's a sign that you're not growing, right? And so you do need to find the next thing [00:24:00] that you are interested in to drive the growth. And, and that will lead to new opportunities. It'll lead to new connections

and

all of those things. What are you interested in now?

What are you nerding out about right now that you, that just gets you so excited about where you're, where the industry is headed, where you're headed, things like that.

Daniel Inocente: Mm-hmm. . I will say one thing though, it's like, okay, it's not just getting bored and then shifting, but having the ability to be bored, but still . Want to do it, you know,

like, okay, you know that something is gonna take a long time to do,

but you know that the end

product is way more rewarding. And so you kind of, you see it through.

Yeah. Um, yeah. But I encourage the students to always like, see your project through, and like, even if you don't like the idea now, like, you know, the vision. So just keep iterating, keep designing, and eventually you'll get to a solution that you feel works with what you initially

thought you were gonna get to. [00:25:00] Um, but I'm, I'm very much interested in, um, the problem of building and building with technology, building smart. Um, I think information technology has a huge role to play in the future. Obviously, it's changing the way that we design. It's changing the way that we create. If you look at, you know, machine learning and ai, these are tools that are transforming different markets and sectors.

But I think, I think it has a huge role. And this is nothing new. I'm not seeing this. You know, like as something novel, but it's been talked about for decades. But I think it has a role to play in the way that we, um, communicate with and optimize our built environment. And so I think, you know, like the idea of, ubiquitous computing, ubiquitous technology and sensing devices and information, um, will change the build.

The urban world will change our houses. We'll change our transportation systems, and it's already doing that. I just got a Tesla and I just love how easy it [00:26:00] is to use. The information's communicating with me how it's slows down and like it, the auto driving is such an incredible feature. Um, but you know, it's, it's communicating with you.

It's make, it's actually connecting with you as a human and augmenting your ability, making your life better. And so I feel like housing could do that. And so I started to venture into, um, prefab and smart, uh, smart homes. And so me and a friend, uh, Partner of mine who used to work with me at s o m, we started a company called Adam.

And, um, we're building our first smart home here in New York. And it's a really cool process for us because we're using manufacturing in the shop. We're using digital modeling, we're using computational design, we're looking at materials, sustainable materials, you know, like passive house certified products.

And then we're also producing a platform to help manage and communicate with the user, um, in terms of like resources, energy, [00:27:00] you know, water, um, all of the resources that we need to sustain a house. And so that's been an interest of mine. Um, and it's also, I think if you think of design, you know, design, when you start to look at it through the lens of systems, like systems of systems, and this is also speaking to the engineering side of what I do is, um, systems of systems thinking helps you really create products.

And solutions that anticipate the future.

You know, it's like lifecycle can, if you design a building now, how do you, how is it gonna be used? How are the occupants going to be able to adapt it? What is the way of tracking, you know, the, the different metrics, um, of how people are using it? And then what is the end?

So what is the end life of that product? Can you design something for recyclability or repurposing or for future optimization?

Evan Troxel: so many times, uh, an architect's. Job on the project is [00:28:00] over when the plans are submitted to a contractor. And you know, there might be some construction administration, maybe, maybe not. Depends on what the client hired the architect for. And then it's like onto the next project. And the next project is, you know, starting at the beginning and going to that point again.

And then doing that rinse and repeat. Seems to me like the things that you were just talking about, give an architect agency to keep the relationship very much alive. Beyond that, turning over of the keys. I, I hate to call it post occupancy, it's actually just occupancy, right? It's not, so many architects will do a post occupancy survey and it's like How, how good is that? That is Marks a point in time and, and it's not after occupancy. It's, it's like the whole idea of calling it, that just seems wrong to me. You can't call it post occupancy, but it's occupancy, right? And it's living with it now. And it's actually seeing if the hypothesis of the design is [00:29:00] actually performing, is

actually providing the things that you were set out to do in the very beginning. And so I think sensors, the, the tech that you're talking about gives us a, it opens the door to continue those conversations to continually improve. The built environment beyond handing over the keys, because we're so risk avoidant, right? We're, we're like, okay, uh, I hope they like it. I hope they don't sue me. I'm working on the next project. And we tend to step away from that responsibility or that possibility, that opportunity to continue to, from an architectural lens, learn from and make adjustments that will continue to make building perform in ways that really serve its occupants. What do you think about that?

Is that, is that one reason why you're excited about [00:30:00] this kind of technology or are you thinking about it from a, from other viewpoints?

Daniel Inocente: Yeah, definitely. So like part of it is design and part of it is, you know, working with a contractor and manufacturer. And then part of it is developing a technology, which, you

know, would most likely be under a different entity, but that technology could plug into the house. And then the house could be the hard, like the, the backbone, the uh, the chassis or the hardware that supports that software.

But it has to be equipped with all those sensing mechanisms and devices.

And then you have to be able to update them and replace them because as we know, um, computer technology is transforming really fast. And so like processor or sensor today, next year is gonna be much better, much faster. Um, but then.

Having knowledge of that. You know, like just understanding how to, how to design around smart systems. That's just like another layer that

you can work with. you know, like we work with different dimensions and so like, there's the, you know, there's the experiential dimension, there's the economic [00:31:00] dimension, the, you know, constructability dimension, all these different dimensions, and we're just adding another one,

So like, I think that's how I see architecture often is, um, we think in terms of dimension and then whatever dimension you as a individual designer are particularly interested in seems to like come out the most, you know, and you can see that in different works by different signature architects, whether it's like, you know, aesthetics or expressing structure or materials, you know, all these different ideas.

But for me that's interesting. It's like how do you collapse all these dimensions and then make it a part of your living environment?

Evan Troxel: Yeah.

Yeah.

I mean, and you've worked in offices that kind of have those different ethoses, right? Like s o m is is one of their, I think, design criteria. One of their values is expressing structure through The aesthetics of the design, right?

Like they don't wanna hide the structure, they wanna express the structure, they wanna show you what makes this building stand up.

And I always found [00:32:00] that to be a really interesting value that they seem to available in every building that I've experienced, that they've done. And you know, Gehry's got Gehry's version of that. And the different places that you've worked have their different version or what, what that list is with the highest priority for them is pretty apparent in that. So when you're working on projects, is, give me an idea of what, what the priority is for you when when you're

Daniel Inocente: Mm-hmm. .Um, so looking back at some of the art projects I've worked on have always started with . So first of course, structure comes into play, but you know, there's always like this domain, which is geometry, especially in large buildings. And geometry is kind of the basis for how you start to break up a, a building system because that geometry plugs into all the different variables.

Um, and you start to export things like, you know, like areas where you put the, the transportation system, like the [00:33:00] cores, the structural on the envelope. Um, and then you start to build on that what is your enclosure system. Um, but for me it's like a combination of looking at, you know, geometry. There always has to be an idea behind that geometry.

It can just be geometry for the sake of geometry. Um, and then there has to be an expression. And that expression, then it, it transforms, it shifts based on the structural idea. And so there's this kind of like emerging quality where you're working with an engineer. And then they give you some feedback on what the structure could be and then the spans of the structure.

And then you start to fine tune the overall form. And then that's somewhat, you know, like dictated by the areas and the mix of program. Um, and then you start looking at things like environment qualities, like day lighting and um, you know, heat cane. And there's all these different layers. And so for me, that's why digital technology, computational design has been so important because it's a tool that I've learned to master.

And then I can plug in all these different variables. I can take, I can take weather data, [00:34:00] I can take, you know, like f e a analysis software. I can take c ft software, I can plug it into my workflow, and then it starts to inform how I think and design. Um, and it's important to like also, you know, have a team with certain expertise to help you, to guide you.

Through that process, whether it's like internal planning, the layouts, or whether it's thinking about, you know, how do you integrate building integrated photovoltaics, or if you're working with like an enclosure system that has metal cladding or terracotta or stone, whatever. And then you start to like bring those elements into your design.

And so, yeah, sometimes I think we can be a little bit forceful because we have an idea and we're like, this is exactly how it's gonna look. And then you introduce some material that doesn't wanna work with that, but you're like, we gotta make it work somehow.

It's gonna intro, it's gonna be complex, but we'll make it work.

So you have to, you have to learn how to be flexible. And of course that's something that we're all constantly learning is like how do you, collaborate and how do you connect with people and give people agents and authorship over your [00:35:00] ideas. .

Evan Troxel: Design is such a series of trade-offs, right? It's, uh, there's, there's like that, that idea, the golden thing that you don't want any occlusions to happen in. And, and then there's the, the realities of money and

physical constraints and what the materials can actually do and how they perform and what the

environment needs. And, and so you're constantly trying to balance and juggle and, uh, make the right trade, make the right decisions about trade-offs that will serve the end result in the best way. And I, I think that's what's so interesting about the challenge of architecture and the problems that we're willing to take on to try to solve and, and. To me that, I mean, that's just like one of the most incredible things about architecture is just the, um, the, the never ending challenges with all of those different pieces that are kind of influencing the recipe that, that ultimately gets baked into the final, the final

building.

Daniel Inocente: Yeah.[00:36:00] And I guess the best, the best thing you can have in a project is a, an amazing site, an amazing client, you know, um, all these amazing like

collaborators where everything works. Yeah.

Everything works together well. Um, and then sometimes you're solving issues that are undetermined, you know, like I've worked on master plan projects where we're thinking about future generations

for like 10, 20 million people,

and like, how do you expand the city in a certain area, and then what kind of infrastructure do they need and what kind of building typologies and how do you, you know, design around that?

And so that's also, that's maybe like a little bit more forward looking, but you need to throw those ideas out there so that you can work with stakeholders and, um, constituents to help get that work done.

And that's not, that's not easy.

Evan Troxel: Yeah.

I, the, the main job of an architect is communication as well as all of those other things. Right? It's a, it's

an underrated skill, but it also something that can be developed as a, as a true [00:37:00] skill to actually orchestrate all of that to,

to turn into reality at some point.

Daniel Inocente: Yeah. Yeah. Absolutely.

Evan Troxel: So you talked earlier about, uh, mastering digital technology. I would love it if you would just kind of go through the tool stack that you have mastered and, and just talk about that, because I think there's a lot of.

Daniel Inocente: Mm-hmm.

Evan Troxel: Questions out there, what tools should I be using? And, and I hate to say the answer is all of them, right?

But they're, you use the right tool for the job and you talked about C f D and f e a analysis and all, and all these different things. And so maybe

you can just kind of run through the different things

that you're, you're using on projects. Not, not just so that we can name, drop what all the tools are, but just to give people an idea of, of what's going out there in the, the tool set of

Daniel Inocente: Mm-hmm. .Yeah, it's just like, um, first, you know, it's like a pencil. Like what kind of, what size lead are you using or whatever

are you using a pencil or a brush or a pin? Um, the tool changes the way that you [00:38:00] design and the way that you think often. And so it's important to keep that in mind. Uh, a certain tool is good for one thing, not necessarily good for

another thing. And, um, I've always tried to stay on top of, you know, software tools because I just know that they enable me. designer to think through the problems. and yeah, definitely. Like another thing I should say is the idea of mastering. It's not something you just, like, let's just say you get good at using a tool, it doesn't stick with you.

You have to practice it all the time. Um, otherwise you stop using a tool for six months or a few months and then something new came on, some, a new feature, um, a new technique, and you're just like trying to stay up to date with these things. You can never stay up to date with those things.

But it's fun to try, you know, it's fun to try that.

Try to stay up to date with the latest and greatest. Um, I've used Rhino a lot since I was in school. I've used Rhinoceros. Um, it's a really incredible tool because it can be used for any, any, any, um, industry. All scales from jewelry to cars, to [00:39:00] airplanes, to buildings, right? Like this is an incredible tool.

You can work in different units, um, you can do analysis, you can do visualization, you can work with plugins, a lot of different plugins for rhinoceros, whether it's environmental I would say it's one of the most powerful tools you can use as a designer, as an architect.

And I've also used Grasshopper. I mean, I've, I've, I've gotten really good at Grasshopper. I've spent way too much time behind Grasshopper. Um, and it's just one of those tools where it becomes like an environment of its own. At some point, you get so good at it that you don't even have to look at the three D modeling environment.

You can just look at the

the

graph

and you know what you're doing. You know, like as long as you don't get any like red, um, boxes, you're, you're,

Evan Troxel: it's interesting to think of Rhino just as a Grasshopper viewer, right?

Daniel Inocente: Yeah.

Evan Troxel: but it is

Daniel Inocente: Um, yeah.

Evan Troxel: Mm-hmm.

Daniel Inocente: you know, the greatest challenge with Grasshopper is like data sets. Like how do you move, how do you structure data on the trees? And then [00:40:00] how do you move that data from one step to the next? Um, because if you do it incorrectly, your computer will crash, or you just won't get the output that you're asking for.

So it's, it's up to you

to

know how

Evan Troxel: problem solving and troubleshooting in there. Yeah.

Daniel Inocente: yeah, yeah. Like how to graph or how to like, distribute the data sets and break it up. Um, and then I've also really enjoyed working in industrial design software like Katia and SolidWorks. Um, these are tools that really help you get into like the detail, you know, like the, the nuts and bolts of.

Of an idea that you have. And at some point, I remember I was working because I used to use digital project when I was at Gehry's Gehry's office, and then I got really interested in using the latest version of Katia, which was a cloud-based Katia. the three D, the three D experience.

And so I started using that. Um, early on I was one of the first users, I was part of this like tribe group with a bunch of experts around the world. And we were invited to conferences in Europe, um, to basically talk about the work that we've been doing using their tools. [00:41:00] And we were helping inform the development of their software and that was really cool.

Um, I have friends who still work at that company and then they, at the same time they started developing a platform which is similar to Grasshopper. Basically it's like a graph, you know, like a friendly user interface, um, for being able to produce models and move data sets between different platforms.

Um, but I think tools like that, you know, cloud-based tools, Parametric computational tools, um, that can absorb a bunch of information very quickly. That can take you from something conceptual, like a basic geometry to something that can communicate a fabrication model. You know, like we talk a lot about in the industry, fabrication ready models.

Um, that's important because when you're designing and if you can take the design from concept all the way through a fabrication model, you're kind of recreating what's gonna be built in the real world. And so you're solving all those problems. And the three D environment helps you learn very quickly on how things work, tolerances, connections, you know, [00:42:00] material.

And that's, that's always been a, an interest of mine. So I, I learned how to use, you know, digital project early on in my career. I used, um, three D experience and then I got into SolidWorks. And I still use Rhino and Grasshopper today. But one thing that I haven't been able to crack is documentation. You know, we always have to deliver data, um,

documents.

And so like Revit is still the, the tool of choice for that. There's no other tool out there that can produce. Graphics, the quality of graphics that Revit can with annotations and dimensions and all that.

Um, but Revit is not, it's not a great, I'm gonna say design tool in terms of like big ideas, but it is a good design tool for solving, you know, as assemblies and technical details and how things come together.

Um, yeah, but there's also a disconnect there because every, nobody will tell you that this, but you know, when you have a Revit model, like a very small portion of it is three D, the majority of it is like a bunch of two D line work, [00:43:00] and it's all disconnected. And then you have like this Frankenstein where you're like, you have a design model rhino, and then you have your Revit model that's trying to like imitate the design model.

And then you have a bunch of drawings that are not connected to the three D environment. So

Evan Troxel: So

the coordination gets lost there, right? Because the, the

connection is broken. Yeah.

Daniel Inocente: yeah, yeah. And then, and then that makes it even harder to change a design because if you go back to your original design and you update that, Then you had it, you know, like

Evan Troxel: Now you're back to AutoCAD, right? Where you have to manually every, every drawing that is referenced from every other drawing. E every BIM manager who's listening to this podcast right now is just pulling their hair out, hearing this, right? Because you you that you never use field regions, you never use you never use model lines, you never use drafting lines.

You, it's like you, you, you draw it, right? And, and it is so hard for people because they're not, they don't have the deep, deep, deep knowledge of the application to be able to pull that off. Or maybe they

don't have the time to invest, figure out how to do that [00:44:00] in the quote unquote right way. Uh, because

the, the the timelines move very, very

quickly.

And then we end up, uh, taking these shortcuts. And then because we didn't do it right now,

we have to redo it later. And, and so we've spent even more time because we don't look at the whole timeline of how much time it actually takes to do it and, and apply the right, um, thinking to that. So we we're perfectly happy spending the time redoing the work later, uh, because we didn't do it right the first time.

But that doesn't make any sense

Daniel Inocente: Mm-hmm.

Evan Troxel: I just wanted

to kind of, uh, include the people who were pulling their hair out into this conversation to say like, I, I, it's true. It happened. What you said happens all the time. And yet, uh, it's, it's almost impossible to fix it because not everybody can get to that level and every piece of software, uh, it's, it's, a, it's a,

true problem of our industry.

Daniel Inocente: yeah, yeah. And I would say it's not like we need to develop fabrication drawings, you know, like we don't always get that scope

or in part, need to do that [00:45:00] level of detail, especially in the

beginning. But it's nice to have a, a way to take information, interoperability from one platform to another, to another,

and then have it all somehow connected.

Evan Troxel: Yeah.

Daniel Inocente: And everybody talks about like, oh yeah, I developed this process and it's like seamlessly connected me from here to here. But I've, I've been in long enough in this field where I know that's not true. , I, I know that a lot of, there's a lot of like workarounds. cusThomization and what works for one project won't work for another

project.

Evan Troxel: the wild West. Yeah.

Daniel Inocente: Yeah.

Evan Troxel: it absolutely is. Talk about the kinds of projects that, that you've worked on. I mean, you, you don't have to go all the way back, but just in the last few years, what are the kinds of things that, that you're doing

with these tools to give people an idea of like what a quote unquote, space architect does?

Daniel Inocente: well I, maybe I go back to first the building projects that I worked on before,

and then I'll talk a little bit about space

architecture. so one project, which was really, um, Interesting to me was a Tower 380 meter tall tower [00:46:00] in China, the Gron World Trade Center. Uh, when I got into that project, we, it was still early stage and it was kind of like a concept developed around this idea of a master plan and a point tower, signature tower.

Um, and then we had this ambition to recreate, and this was a metaphor, you know, it's like inspirational, but the idea of like the rice fields and the flowing hills onto the building facade. But there was also other performative factors to that, which was about confusing the wind and cladding the external skeleton to optimize the lease bands and reducing the amount of carbon from the structure.

So there was a lot of other ideas behind that. But the, the enclosure system was really complex. Um, it was double curve geometry, um, all meant to be, um, powder coated aluminum. And there were these mega panels that were spanning like 3.2 meters. So, you know, like much taller than you. And me and, and these panels, they had to be built, um, locally.

And so fabricator at that time, they were just testing how to build this thing. And basically what [00:47:00] they had to do was create like a form work out of, you know, like just test it out, plywood. Then they would like press stamp it, press stamp the metal,

and then they would have to like, you know, basically weld it together and then like finish it, sand it.

And then eventually they came up with this mock-up. Um, and so the modeling of that, just like the digital representation was a really interesting exercise because we had to figure out how do we optimize that geometry so it can be repeated

and a certain number of

families.

And then

Evan Troxel: ask you

about that.

Daniel Inocente: how do you, yeah, how do you work with, um, the enclosure system and then the glass units because the building was tapering had to change as you're going up.

And so you had to like group the building into different segments. Um, and so all that was a part of a three D model that I developed. And then we, we gave that to the, um, the builder and the fabricator, and then they use that three D model to produce. A lot of the components of the building.

Um, and that was just one part of the process.

And we also used that model to document the project, and it was in, you know, in Revit. And we were just like, I [00:48:00] was linking it directly and pretend there was a change, I would just shoot the information back, um, working with the engineers to look at the column sizing because for a tower like this, as you go up, the concrete structure gets narrower.

So as you go up, it has to like step.

And then the engineers would give us, they would give us that information so that we can plug that into the, into the Excel. And then my Excel fed into the Grasshopper script, which spit out the geometry for the structure.

Um, but that was one project. So just thinking, you know, like how, how do you design something of that scale?

How do you work with a manufacturer? What kind of level of detail do you have to develop your model to? How do you document it? and then another project I can talk about in terms of space architecture, um, very dis, very dissimilar, but. I think there's some, like, some ideas I can connect between them is so the idea of, uh, a large habitat for the Moon Village.

This was a project that I spearheaded where, um, I was very fortunate at that time I was going to space conferences again, [00:49:00] connecting with people. had already met a lot of people when I was working previously in the space industry years before. And so they invited me to come to a space event and I said, okay, I'm gonna come and talk to people and learn about what's going on.

And, um, I got to meet some key individuals there, including the head of the European Space Agency at that time. And we had a fun discussion about bridging two different worlds. He was actually a civil engineer, um, in, you know, in his education. And so he, he just loved the idea of working with architects, um, to think about large scale developments beyond Earth.

And we basically struck up a partnership that evolved over a series of meetings, and eventually we started to work on a concept for a . Space habitat. And that space habitat is that vertical four story habitat that, um, that you see in, if you just search Moon Village, um, east side, you'll, you'll see that project.

And that was when I was working at SOM. And so me and, uh, a few others at the company were working on this project. it was a really,[00:50:00] enriching experience because I got to connect with a lot of people outside of my field. people from material scientists and engineers to propulsion experts, you know, radiation experts, just like things that we never talk about in the building industry because we just don't need to.

so that really opened my eyes up to what it takes to build infrastructure and space. It's not just about habitation, you know, it's about, um, protecting yourself from the outer space environment. It's about the transportation system that your concept has to be designed around, because that limits the mass and the scale of your habitat and then the destination.

How do you get it down to the surface of another celestial body? And then how do you transport it? What are the sequence of events to getting it from, um, being on the surface to being fully occupiable? And these are all actual like problems that we are gonna have to solve when we start sending humans back to the moon.

And so I got to think about these problems, um, in, in a certain level of detail, but not too much. And that was really amazing for me to just come up with [00:51:00] an idea that was widely published and accepted and celebrated and people thought it was, it was a cool concept, even though it's a little future forward because the habitat is pretty large.

Horse stories is not something we can deliver anytime soon.

Evan Troxel: Yeah.

Daniel Inocente: Yeah.

Evan Troxel: Can you talk about that delivery? I mean, it, it seems like, you know, there's payloads in, in. Transport and there's logistics and, and you've also kind of mentioned three d printing where you would use available materials, you know, that that would be localized to the site, I assume. But all of that is, is gotta be a huge topic of conversation early on in these projects rather than figuring that stuff out later. Uh, there, there's,

there's so many things that are just based on logistics alone. I would imagine

that, that as part of that conversation so early on

Daniel Inocente: Mm-hmm. . Yeah. It's like, uh, you know, real estate location. So there's also location on the moon that's optimal for resources, for access to daylight, for power,

[00:52:00] um, for access to water, ice, and also for geologic interest. So like the premise of going to space, going to the moon, um, it's a combination of things like industry, technology development, science from governments, and then also.

You know, people just are excited about it. So tourism might play a role in that in the future, and it might be actually a very important role because we need to find a way to subsidize going to space,

um, in big ways. But yeah, the resources in outer space are vast. You know, we're always talking about, limitations of earth and how, you know, we, we need to like control our consumption

and how we're transforming the, the planet.

But if you stop to think, you know, the, just the inner solar system could support, you know, like trillions and trillions of people. If we, we learn how to harness the resources of outer space,

and that's one of the, the most interesting things you can start to think about. So like how, how can we make useful resources in outer space?[00:53:00]

Well, maybe we can't bring them back to earth, but we can definitely go to outer space and harness energy. Can we bring some of that power back to earth? Or can we develop technologies as we're going out there that can be used? In terrestrial applications, one of the greatest, um, exports that we'll have from going to space is, um, patents, you know, like new ideas, new technologies, new patents.

And so that, that would definitely be a measure of, progress. Um, like in the, during the space race, I think that during that period with the most number of patents and technologies developed, you know, in the history of the

us So that, so that's where, that's where I think it's also interesting.

It's, it's, challenge for us to innovate. Um, but resources will play a huge role. And on the moon, for example, if you can harness water, ice, you can turn that into fuel, you can turn that into oxidizer, you can turn that into, um, consumables like water for humans. Um, and then if you look, if you can learn how to harness the regolith, you can use that for three D printing.

[00:54:00] You can use that for producing metals. There's a lot of glass in the surface as well. So, All of this will take time. It's gonna take a lot of invention. 'cause we don't have any machines that can survive the outer space environment, especially on the moon

where the red lift is abrasive and if it gets into any gears, it damages the gears.

There's a lot of information about this and during the Apollo missions and how it damage a lot of like the suits and the gears and you know, the materials. So there's gonna be, uh, a huge, you know, need to, to innovate there. and resources are just the beginning.

the other side is, can we develop sustainable community?

Um, we have to rethink how we design spacecraft for habitation. what is the most optimal volume for people to live and thrive for a certain duration? An extended duration. You know, like the moon missions were only lasting, um, a couple

days. A few days. Where, um, in the future we're gonna want to have people go out there for months, [00:55:00] maybe years.

Like on the i s s, what's the average 180 days? You know, I think people have spent, um, as long as a year or more up in the i s s, but then if you want to go to the moon, it's quite, you know, it's not that far, but still it's a distance. And

if you go there to do any meaningful work, you're gonna wanna stay there for months

to develop technologies and to prove, um, that things work.

So that's where space has space architects come in and we can come up with ideas like, how do we optimize the use of volume? How do we co-locate spaces and functions? And then what is the, the optimal, you know, like design configuration for space habitat that has a certain purpose. Um, and so there's a lot of layers that we can plug into.

It's kind of like the role of the architect. We a, we're, we're helping architect, um, a mission, a vision, and then the integration of all those technologies into that space for human

for human occupancy.

Evan Troxel: Right. What, what inspires you? I mean, not just visually, but, but [00:56:00] technologically. I mean, there, I, I would assume that a lot of sci-fi does a really good job of kind of inspiring people to think beyond traditional forms and, and the bounds of, of that we actually have in physical, in the physical world now. Um, but it's in, it really interesting to me to see devices emerge, transportation systems emerge,

Daniel Inocente: Mm-hmm.

Evan Troxel: was conceptual imagery for, you know, way, way, you know, decades ago that's now happening today. For you, what, what is inspiring is, is there imagery that exists that's inspiring you that, that you could point at?

Daniel Inocente: I wouldn't say imagery, but more, the hard work of certain individuals out

there. I mean, I. I'm just gonna say it, but SpaceX is doing incredible work and the idea of going to Mars and building a, a ship of that scale, I think that's super inspiring because[00:57:00] if you can get, you know, that amount of mass to space and to another celestial body, it just, it, it kind of hits the reset button on what we can design.

And so for, for anybody who's thinking about sending, you know, equipment or technology or habitation to another, to the moon or to Mars, you can start to come up with different ideas.

Evan Troxel: Yeah.

Daniel Inocente: Even satellites, I mean, even satellite missions, you know, like we used to be able to send small satellites and um, like the Hubble Space Telescope has brought back a lot of, a lot of great science and imagery.

And then now we're looking at, um, you know, larger and larger, um, telescopes that can identify other habitable worlds and tell you what the characteristics are.

And can we, you know, how many, how many habitable worlds are out there? That's another cool topic. It's like, can we . Can we, um, prove that there's life beyond Earth?

And that's one of the premises we're going, you know, to Mars. Like, we're searching for life signs of life.

Evan Troxel: It becomes [00:58:00] the next jumping off point, right? It becomes the new reset of, okay, now we can look from here. Instead of looking from where we are right now, gives us a new perspective. It's really interesting to think about, uh, I'm not sure where I got this idea. I know it's not from my own brain, but that the whole idea of the universe is always expanding and the universe is always shrinking in the way that we're always designing more powerful tools, whether that's a telescope or a microscope, to look at smaller and smaller things. Every time we do that, we just find out that there's more out there. I think that is so

interesting, like there is no end. Magnification wise or telescopic, like, we just keep finding smaller and smaller things and we keep finding bigger and bigger bounds to everything. I think that is so interesting and, and for us to, in academia place any kind of boundaries on what is possible for those graduates to go into or achieve is completely ridiculous to [00:59:00] say, you know, these are the, these are the firms that exist today and therefore you need to get ready to work at those firms.

Absolutely ridiculous. This is the software that exists today, so this is the software that, that, this is the only thing you'll ever need to learn. I don't know that anybody thinks like that, but I definitely know there have been people who say that and have said that kind of thing in the past, and it's just incredible to me that there is no, there are no bounds to any of this. And to find a trajectory of interest

for every single individual who's interested in

pursuing these fields, uh, the, it's wide

open there. There's just so much possibility.

Daniel Inocente: life is such a short journey. Like you have to make the most of it because you're here and then you're

not. It's a, it's a brief moment, so just follow what you enjoy and, uh, you know, just make careful decisions along the way. Um, like I have a family now, I have two kids, and so now my choice is a little bit more calibrated than before

I have to think about them too.

and it's, uh, it's important [01:00:00] to just pursue your, you know, what, what makes you wanna wake up and do the work that you do.

Yeah.

Evan Troxel: Lovely way to end this podcast. I think right there that you just summed it up so, so beautifully. And, uh, Daniel, it's been a pleasure having this conversation. I'm hoping we can share some images, uh, people I think at this point will have either seen them and the vis video version of this podcast. Or, uh, if you listen to the audio version and you wanna see some of the, the imagery of what Daniel was talking about, check out the YouTube version and, uh, I'll put links to everywhere you can find Daniel online in the show notes. And Daniel, is there anything else that you wanna tell the audience or, or let them know a place they can connect with you?

Daniel Inocente: Yeah, feel free to go on my website, connect with me, and if you're interested in a particular topic that just, uh, reach out. I, I always respond. I think that's always, you know, it's important for me to respond whatever questions. I, I love working with students and professionals, experts, anybody.

Evan Troxel: [01:01:00] Making connections. All right, Daniel,

thank you so much. I appreciate your time today.

Daniel Inocente: Thank you, Evan. Take care.