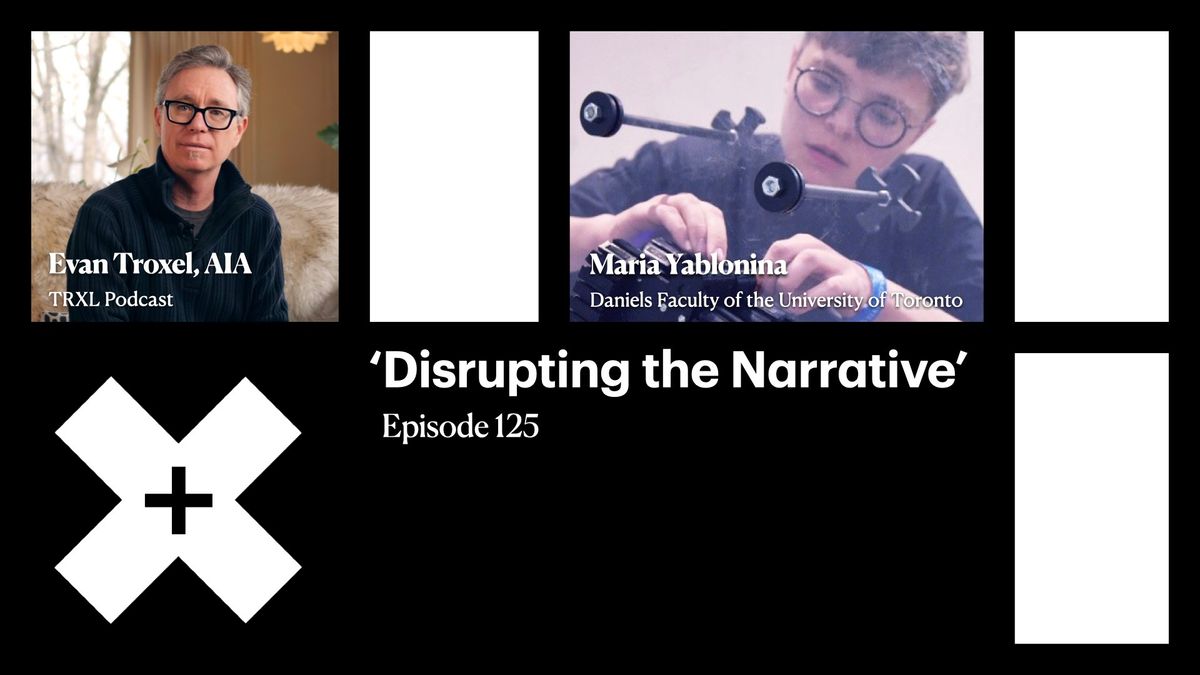

125: ‘Disrupting the Narrative’, with Maria Yablonina

A conversation with Maria Yablinona.

Maria Yablonina of the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto joins the podcast to talk about robotics in architecture; specifically her work in developing tools and machines to aid in construction projects where she emphasizes the importance of both considering practical applications and involving workers in the development process. Maria also highlights the need for interdisciplinary collaboration and the importance of empathy and literacy in navigating different fields.

Episode Links

- Maria’s website

- Maria on LinkedIn

- Maria on Twitter

- Maria on Instagram

- Maria’s faculty page at U of T Daniels

- The John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto (U of T Daniels)

- U of T Daniels Faculty on LinkedIn

- U of T Daniels on Twitter

- U of T Daniels Faculty on Instagram

Connect with Evan

Watch this on YouTube:

Full Transcript

125: ‘Disrupting the Narrative’, with Maria Yablonina

[00:00:00] Welcome to the TRXL podcast. I'm Evan Troxel, a little bit of housekeeping. Before we get into this episode, I'll be attending a couple of upcoming AEC conferences in the next few months of 2023. Confluence in October, which you'll hear a message about during this episode and Autodesk university in November. If you're going to either have them send me a message on LinkedIn email or social media. And if we're not already connected, you can find links to those in the show notes of this, and every episode on my website at trxl.co. All right. In this episode, I welcome Maria Yablonina is an artist, researcher and designer with a strong interest in robotics and digital fabrication techniques. And she is currently focusing on exploring potential fabrication techniques, enabled through introduction of architectural specific robotic tools for construction and fabrication. Her work includes the development of [00:01:00] hardware and software tools as well as complimenting material systems. She is currently an assistant professor at the Daniels faculty of architecture, landscape and design at the university of Toronto. Which is also referred to as U of T Daniels. In this episode, we talk more about robotics, specifically her work, developing tools and machines to aid in construction projects where she emphasizes the importance of both considering practical applications and involving workers in the development process. Maria also highlights the need for interdisciplinary collaboration and the importance of empathy and literacy in navigating these different fields. This was a great conversation. So without further ado, I bring you Maria Yablonina.

Evan Troxel: I'm here

with Maria Yablonina today,

and [00:02:00] I welcome you to the podcast. Thanks for coming.

I.

Maria Yablonina: Thank you so much for having me. It's a pleasure to be here.

Evan Troxel: Maria, tell us about your trajectory, how you've gotten to where you've gotten and why this work is is important to you.

Maria Yablonina: Uh, very good question. Uh, question I ask myself quite a lot. Um, I'm trained as an architect, which I know. I, I, I've been listening to a couple episodes that seems to be a thing for people on this

podcast. Like I'm trained as an architect, but, and then whatever follows, follows, um, yeah, I got my undergrad degree in architecture back in Moscow, which is where I'm from.

And then I moved to Germany for my master's studies where I was really fortunate to, um, study in Stuttgart at the Institute for Computational Design, now named Institute for Computational Design and Construction

with Professor Jimenez where. I sort of, um, I joined because I was interested in computational tools and I was sort of [00:03:00] dabbling, um, in my own time with coding, um, kind of learning processing and thinking about how that impacts design processes. But then I landed in Stuttgart and fell absolutely in love with robots. Um, both as these really compelling creatures that are, you know, quite versatile and can do a lot of things. But also, uh, I fell in love with, um, Kind of a flavor of practice where I got to make my own mechanisms and my own programs. And, uh, I like to joke that I became a roboticist by accident. Um, and yeah, it sort of took me away. So now after my Stuttgart time as a master's student, and I'm later as a PhD student, I'm now an assistant professor to Daniel's faculty of architecture, landscape and design at the University of Toronto, where I'm also a member of the Robotics Institute as a faculty member. Um, so I do research and I practice as a [00:04:00] roboticist, as an engineer, as an artist. Uh, I wear a lot of hats.

They're all,

Evan Troxel: was gonna just say

that

Maria Yablonina: yeah, they're,

another joke that I really like to default into is that I specialize in wearing many hats and feeling anxious about their size and their placement on my head, and whether or not I'm a real artist or a real roboticist or a

real engineer.

But the space in between many things. I also find very productive, um, as both. I enjoy being in that practice space and I find that it, I kind of have this privilege to be able to translate between fields and talk across disciplines, um, and hopefully influence across disciplines.

Evan Troxel: I can see that being really a key driver for, especially in academia. That's really great to see the cross-disciplinary stuff going on there, because I think going through architecture school, I went also to a college of environmental design and it was multi-disciplinary and urban [00:05:00] planning and landscape, and there was an engineering, school on campus as well, among many other schools.

But there was no cross-disciplinary action that actually happened there. And so when you hear, I, I don't know if that's just something that's happened more often or if it really depends on the school, but it's interesting to hear it when it does happen because you are able to bring more collaborators to the table during the curriculum planning, I would assume, but also kind of figuring out where the curriculum is going, where it's, you know, because I would also assume as being a professor previous, in a previous lifetime of mine as well, you're always looking as what, what should you be teaching?

Where do, what do we need to be incorporating that's changing in the, in, in industry, in the professions that could be driving, you know, curriculum development. So that, that's great to hear that that's actually alive and well where you're teaching.

Maria Yablonina: Oh yeah, absolutely. It's, it's not without its complications. And I

think these days, interdisciplinarity is [00:06:00] kind of a term that we all love to latch onto, uh, which doesn't mean that it's easy. It really often feels like translating between different languages and between different value systems

or evaluation criteria. Um, which again, comes with its own politics that are not always as simple as just saying interdisciplinarity, yay.

And, you know, closing the box at that point. Um,

Evan Troxel: Right, right. Yep. I can definitely see that as well. It does come with some ex, like, just just the idea of faculty department meetings. It just kind of gives me the shakes to think about and, and when you're trying to

wrangle or herd the cats of various departments and schools together to, to have these conversations has gotta be a, a, a tough experience because number, it's hard in, in corporate life as well just to get everybody at around the same table at the same time.

But when there's these various, uh, things pulling at everybody and they all have their own [00:07:00] motivations and their own problems that they have to solve and their challenges and their courses that they're teaching, that's, it's, there's additional layers of complexity there for sure. It sounds

like.

Maria Yablonina: Oh yeah. Absolutely.

Evan Troxel: So one of the things that you said is that you, you act as an engineer and you said you like to build robots. I and you like to build these mechanisms and I think that sets you apart differently in my mind from some previous guests in, in that they're a lot of times roboticists, uh,

especially in AEC, are.

Getting

tools and machinery that are developed by, you know, a, a company that specializes in that. And the thing that you're talking about is actually making your own mechanisms to do the things that you want to do. So you're kind of controlling the whole ecosystem there. You're not just getting this thing and then figuring out what to do with it, but you're actually purpose building it to do the things that you want to do.

I would love to hear all about that because I, I, that to me, [00:08:00] as somebody who likes to tinker and take things apart and build things and make things and, and remodel spaces or design architecture or work on automobiles or whatever it is, I, I love that too. And so I'm really interested to hear kind of that part of your story and where that comes from.

Maybe let's go back, like where do you get that from?

Maria Yablonina: I get that from a sort of naive and almost accidental decision. Again, going back to my Grad studies as a master's student. In the final year when we were supposed to start working on our thesis, we had access to one robot arm and there were 16 students. And despite the fact that I was really interested in working with robot arms, I was like, this feels like a very kind of limited resource.

So I'm gonna be very strategic, which again, in retrospect is pretty silly. Uh, it's like I'm gonna be very strategic and kind of create my own tools to work with so that they can be mine and mine [00:09:00] alone. Which was pretty naive and a little bit, um, dangerous. But that got me into this practice where, and by that time I was already designing some end effectors.

Like I had a little bit of experience with things like Arduino and a little bit of mechanical design, but I was really coming into it from a completely self-taught, here's a project, these things need to be done, I guess I'm just gonna figure it out.

so with that very little experience, I kind of just dove in and started putting things together.

For the longest time, they did not come together the way I anticipated. They were very actively falling apart over and over again. Um, So, but then through that process, I feel like I got to a place where my whole understanding of what robots and machines and architecture can be. 'cause there's so much, um, if we look at the narrative around digital fabrication and computational and design that's been developing and existing in the past [00:10:00] almost 20 years. So much of it has been around designing and fabricating these beautiful geometries or

using materials that we've never been able to use, but it all kind of ends up being very shiny, uh, like in this beautiful lab that is spotless and fully controlled environment, of course, um, making these beautiful objects that are complex and kind of unfathomable to a human designer,

uh, in the before times. Um, but there's something about that that for me, in terms of narrative doesn't quite integrate into the reality of how we occupy architectural spaces and how we occupy buildings. Um, it's rarely really building beautiful things from scratch. A lot of the time it's you show up in a space or you show up in a building that is already in place and figure out how to either add to it or demolish or reconstruct. Um, through this again kind of [00:11:00] naive and almost accidental decision, I ended up forcing myself into the space where I started thinking about architecture more as a site, less as an object that needs to be designed from scratch and the kind of traditional architectural narrative of, you know, the brilliant architect shows up and there is nothing and now suddenly there is a tower or whatever.

and yeah, I think I kind of got over that narrative. Um, And I'm more interested in working with stuff that is already here and kind of figuring out ways to care for objects and buildings and maintain them, um, rather than pursuing some shiny outcomes.

Evan Troxel: I,

I, would love to hear some, I, some examples of what you're talking about there. I know that you've worked with kind of this idea of weaving

and robots that are transforming space potentially over time, like winding and unwinding different assemblies,

and I, I, I would love to hear from your [00:12:00] description of what some examples of the, this blank slate, but not really kind of a,

a, some examples of that.

Maria Yablonina: Um, well, interestingly enough in that, Again, the, the decision making, uh, moving away from industrial tools into sort of, um, d I y tools or self-made tools. I was also influenced by a research project that I was doing a year prior to that where I was looking at spiders and the way spiders build their webs.

Um, and of course there's so much to be inspired by there, both in terms of Like if we think of a spider as a machine, it's very small, but it builds these huge, extremely complex and very functional, um, objects.

Evan Troxel: Mm-hmm.

Maria Yablonina: But also the, the species that I was working with, uh, like we had a few spiders in the lab. We were tracking them in three D trying to analyze the sort of construction sequence, if you will.

So

[00:13:00] like what's the first form work and then how does it add different functions to different parts of the web? 'cause there would be a separate area of the web that is for hunting, uh, or like capturing prey, a separate area for nesting that is more dense and kind of enclosed. Um, so we were trying to analyze that, but also the species, uh, that we were working with, um, Has adapted, has like evolutionary adapted to work inside human spaces. so it actually really wants to be in the basement or in the corner behind the cupboard. Like it, it learned to treat human recline, human environments as its own construction sites. Um, so that was also a big part of, uh, the, the spider story that really influenced me. So I started thinking about, well, if I am building my own tools, both from a very pragmatic point of view of budget and scale, it's like, well, they have to be small. Uh, they have to be made of parts that I can again [00:14:00] afford as a student. Um, but I was really interested in exploring mobility as in opposition to the robot arm that always has a very limited reach,

uh, like

I find it interesting when people talk about robot arm versatility. Like, yes, they are versatile. You can attach any end defector and you can work with any material as long as the object that you're making is sort of car sized,

because they're not actually universal machines,

they're machines for building cars. and, and again, that narrative is something that I really wanted to disrupt. So I started thinking about mobility as a way to scale things up, uh, as a way to really travel around the environment and interact with it.

Um,

and obviously one can travel on the floor, but that again, limits the work envelope of what can be built.

So from that, this idea of having wall climbing robots happened, so, The initial vision was what if I come into a room, I see what the room [00:15:00] offers, so there, there will be surfaces and features, and I can deploy these kind of discreet, but interacting machines onto the walls, and then they can start occupying the space and add to it or remove from it. so the first, um, I guess three or four projects that followed my final dissertation were all dealing with weaving processes as a fabrication method, which was both because it's a really convenient fit. Um, like a small robot has very small payload. It can travel technically infinite distances, but it cannot really carry as much. Um, and filament material like string or rope or fiber really matches that. It's infinitely long or infinitely short. So it scales in both directions. And still quite lightweight, um, compared to the space that it can, the volume that it can occupy and the volume that it can create. So at that point, I guess the choice [00:16:00] of material became strategic and pragmatic. But then later on, as I started develop further developing this practice, I again started noticing all of these layers of metaphor around softness. Like the objects that I create are always temporary, they're

always removable and sort of F you can weave and unweave and then re-weave and continuously reconfigure what the object is or what the space looks like. But also from the point of, um, like history of technology and history of robotics, it's definitely pulling threads from the first computer being the JA card loom, the way that female or like traditionally associated with female labor craft practices have turned into computational practices and engineering and the kind of the historical emissions that happen there. I feel like all of those references and all of those layers of metaphor also live in my work. Um, so yeah, and then it turned into this [00:17:00] practice of showing up in a space and figuring out what Robot works in said space, and figuring out how to occupy it.

Evan Troxel: It's today's the first day that I learned that spiderwebs have a program and , I've, it's kind of obvious when you, when you look at it now, it's like, well, yeah, there's like this, the place where they, they go into kind of sleep or, you know, like the, the

protected zone and then there's these other zones, but never literally thought about it like that before.

I think that's really interesting. And thinking about a, a space potentially having its own program as well, like obviously buildings have program, right? There's, there's all these different types of spaces for different functions in buildings, but then each building with this layer that you're talking about, kind of adding or incorporating into having the ability to then kind of design and deploy a system for creating

Subsets of, of differentiation within a space that could be temporary. [00:18:00] Maybe it is, maybe it isn't. But I think that's a, a really interesting way to kind of approach architecture. Can you explain for the audience, and, and for me, like what, what is the purpose of doing this in space? Like what, what are the goals or different kinds of goals that you're looking for achieving in these spaces with these kind of woven assemblies of the material that you're using and using robots to do it?

Maria Yablonina: Um, well with a series of projects that I'm referring to that were mostly done during my PhD time, uh, so the series of these kind of woven or

wound rope projects, um, they were all sort of research vehicles to understand, uh, well a, is it even possible to have these extremely task specific machines, uh, that are designed for the space and for the material and for the fabrication process, um, create enough of a spatial influence, uh, To inform how people [00:19:00] occupy the space, how people move through it. Um, so in a series of these sculptural objects, some are kind of furniture scale, some are larger, some are purely sculptural. Some have a bit of a more of an enclosure sense. Um, one of my favorite audience feedbacks, um, I was showing one of the projects in an exhibition context and we were running the machine system live.

So after the exhibition is opened, we would prefabricate some parts of the woven structure, but then we would continue adding more and more layers so that the visitors who would show up to the opening, they see it in one state in the first hour, and then the state is completely different

and . You know, denser in the next hour, et cetera. And I sort of, as I was running things, I overheard just behind me two visitors whispering. It's like, it's like inside being a huge JA card loom. And I was so happy.

I was like, yes,

that is exactly where I'm going for. Um,

Evan Troxel: Interesting.

Maria Yablonina: so [00:20:00] yeah, it's both investigating what these systems can be, uh, in terms of hardware and software components such that they can functionally occupy a human environment. Um, how do these systems Coexist with humans, both in terms of safety and in terms of how people feel around them. Like some of my machines ended up being very, very loud 'cause they have these vacuum motors, so it's not the most pleasant,

um, thing to kind of co relive with. But others are pretty quiet and very gentle and they're kind of remain at the periphery of the space.

Um, and then seeing how these objects as they change throughout the quote unquote fabrication time or maybe performance time, um, how do they change the way people occupy that space next to this thing that is kind of continuously moving and evolving? Um, so yeah, I, I was really interested in these thoughts of preoccupation. Um, [00:21:00] instead of, again, the traditional architectural narrative where you build a thing and then people come in and live in the thing.

It's more of a continuously evolving relationship between the space and the human. Um, and then after that series of projects, uh, which are currently, I wouldn't say I'm done with that story, but they're a bit on pause. I'm now working with still climbing robots, but in more of a, again, reconstruction and repair scenario. So I'm collaborating with, um, a fabricator company to develop, again, a very, very custom, very Task specific and actually building specific robotic tool for laying out, um, construction instructions. So it's sort of like dusty robotics, but on a very complex trust system, uh,

for repair application where

we're kind

of, uh, [00:22:00] laying out points for facade panels to be attached to a three-dimensional truss, which is very complex and

hard to kind of even know where things are

Evan Troxel: Yeah, I could imagine. I, I'm really interested in talking about that. Before, before we jumped out, just before we do the, the, the winding robots and kind of the, some of the practical applications. I think I saw an example, I guess it maybe it was a hackathon or something from, I don't know, five or six years ago.

And I think Brian Ringley was a part of that with you, and you guys had this kind of aluminum structure and you were, you were doing some different loom type winding on this. And then the idea of it, I kind of, Creating separation between space in different levels of porosity, I guess maybe is a way to say it.

Uh, that where you could have it be more private between two spaces or less private. It even seems like you could have like the users the occupants with a dial and kind of[00:23:00]

dialing it back and, and so, you know, the, the idea of of building something and deconstructing it, so constructing it and then deconstructing it, or that just constantly kind of being a negotiation, uh, in space is really interesting way to think about space and the delineation between types of spaces.

As, as it, it being on a spectrum, it doesn't need to be set.

Maria Yablonina: Mm-hmm.

Evan Troxel: Once and and done. I think that's a really interesting way to kind of think about architecture. Are there examples out there that people can experience where this is actually happening in public or is this still like the kind of thing that's in a lab and it's really the kind of stuff of PhD work that's that's happening behind the scenes?

Maria Yablonina: I would say it's still very much lab adjacent. Um, and, and again, in my work, I've always made sure to every single system was built for [00:24:00] an exhibition

event. Um, so very little of my machine systems have been designed without the space in mind. Um, and again, because I think that the process and the narrative around that process, to me is very important, where the machine does not come first, the side comes first.

Um, and in the kind of evolution of these projects, I've developed wall climbing machines that can climb on a sort of normal wall surface that is painted and finished. I've developed machines for climbing along, um, sheets of materials, and they're sort of double-sided and they clamp onto a flat sheet. Uh, so you could think about windows, you could think about facade panels, separators in interior spaces. Um, I've made a few iterations of rail machines that would be attached to, say, columns and beams in a space and turn the whole room basically into this. [00:25:00] Not quite a three D printer, but like a fully

occupiable by machine space. so I'm really interested in, again, converting, uh, sort of mundane architectural elements into almost a substrate or

a support structure for a robotic system.

Again, in opposition to maybe industrial robotics or even a C N C machine that does not scale.

So, um, like in one of the projects where I'm using As like a very uh, low weight plastic and aluminum rail and I'm attaching it to the column and beam system within the building one can imagine. Um, so yes, it is tailored to that space, but then I can take that and I guess the metaphor of tailoring a suit really works here.

I can take that suit, bring it into a new space and re tailor it to either scale it up or scale it down. And it still works within reason of course.

'cause there are limitations inevitably. Um, but it's pretty flexible and can be redesigned [00:26:00] or just slightly adjusted to fit a new environment.

Evan Troxel: It makes me

think of like a, a concert venue where the, the stage structure is tailored potentially for different venues, right? Because of the size or the layout or the shape

of the bowl or whatever. And there's like a certain amount of adjustment built into the, the structures that they build. But they, they put 'em together and then it, they do the performance or performances in there, and then they take it down and they go to the next place and they put it up with adjustments potentially, and, and it serves.

It serves the space that it's occupied in inside. I, I know it's not maybe the perfect metaphor because a lot of times it is just kind of, uh, assemble it just like this and then take it down and assemble it just like that again. But it, it seems like there's potential there for like you're talking about where you can actually tailor it to the thing that it's going to be inside of.

And it, it reminds me of being an architect and doing the kind of [00:27:00] projects that I did in the public space, which are classroom buildings. And for that was a, a big part of it. And it was interesting to me to watch the trend of those classroom buildings just being like, almost like a black box theater where it was like, The space needs to be able to transform and adjust to future things that we're not thinking about right now that could need to be taught in that space later.

And so the trend was to make the spaces more and more and more generic. But, but the other way to say that is flexible, right? And, and what that enabled them to do then was to transform that space into whatever they needed it to be. Because a school is gonna be standing for a very long time. Technologies change and the space needs to adapt to new curricula, for instance, right?

Uh, and different sizes of classrooms or number of students or any one of those things. And this is a very interesting way to do that. I mean, we're not just talking about sensors [00:28:00] that are IOT devices that are monitoring something, but they're actually contributing to

Maria Yablonina: Mm-hmm.

Evan Troxel: the space and the way that, that, that people interact with that space.

I think that there is this interface, kind of this middle level. Interface

between occupant and space and the, like, the potential transformation of space is really interesting. Where did, where does that interest really for you? Where does that come from? I mean, this whole idea of using a building as a, intermediary, uh, devices to do things with that space that, that is so specialized and, but it also seems like such an obvious place for architects because there are so many buildings that are, need to be adapted.

Adaptive reuse is a huge topic and, and not just long-term adaptation or transforming a really old building into something that works now or changing an office building into housing, but something that is much more adaptable much more often. I, I am really [00:29:00] in intrigued in where you. How, how you kind of pieced all that together as a, as a something to, to chase after.

Maria Yablonina: Um, that's a really good question. I'm not even, well, I guess I've always been sort of fascinated by these ideas of like buildings as machines, going back to, I dunno, Cedric prices work and going

back

Evan Troxel: Mm.

Maria Yablonina: um, like Archigram and the way they cheekily critique, uh, Kie by literally like, oh, machine for living.

You say, well, here you go.

Um, which I always really appreciated. Um, but, and I guess again, this layer of interface in between that is not quite a building,

nor is it a furniture. It kind of, yeah, it, it sits at the, in this blurry

boundary. Um, and also in a way that it interacts, it kind of sits in a blurry boundary in a way. I. [00:30:00] It's in like the most practical way it adapts for new programs. It sort of serves, if, if I could use that word, but in the same way, it, it is its own creature that has its own agenda. And sometimes it's like, you know what, I'm just gonna weave this whole space shut. And you figure out how to deal with it. Um, and like thinking about these, uh, machine systems as really Companions and co occupants, um, I think is a really important and interesting way of rethinking our interaction with technology 'cause, um, and, and I guess partially my, again, my interest in developing my own systems comes from some discomfort with the history of industrial automation.

And I feel like every time I see a robot arm do something, and I, I work with robot arms a lot. Like, I'm not saying that I, I, I don't love them. I still do. I teach them a lot. Or like I teach with robot arms a lot. [00:31:00] Um, but every time I see them doing even the silliest thing, there's somewhere layers and layers and layers of metaphor. There's sort of a For this factory back in the beginning

and in that history.

And I'm not sure that I'm comfortable with the politics that that brings in.

Um, and I feel like as architects having adapted those technologies in a very kind of apolitical way, we're digging a hole for ourselves a little bit again, where it's like, but why are we, why do we continue to make buildings that still have that energy of a car?

Both in terms of like, it's a luxury item and it's really beautiful and it's made of new materials. whether in, um, again, my sort of accidental pursuit, what I ended up having to do is spend a lot of time in very close proximity to space, to actually, not even just the space, but the surface, like the, the rough wall, the crooked relationship between like beams and [00:32:00] columns and peeling paint. And it's all completely un uncom computable. And the only way of dealing with it is then programming some flexibility back into the machine system, both in terms of hardware, being able to kind of adapt and be okay with bumps on the wall and be okay with things not aligning perfectly. And of course, software where it has to continuously correct its own actions depending on sensor input. Um, but then again, in a larger framework of what does that mean to design that way, I feel like. it creates a certain humbleness towards the space and humbleness towards what there is. And in making a machine more flexible, I think as a gesture that is a gesture of respect and care for the space that I'm occupying. Um, and I would love to see more of that, uh, in the field in general where let's not forget why we're [00:33:00] here. We're here to really deal with spaces that we occupy as humans and spaces we designer as designers, but also, um, we're dealing with climate change and complete like huge shifts in how construction and other industries must adapt. Um, and if we don't change our priorities kind of away from the shiny towards the care, I think

we're digging ourselves a very dangerous hole.

Evan Troxel: Mm-hmm. , you mentioned this idea of autonomy and the, the robots, uh, having a mind of their own potentially and just weaving a, a space shut or something.

Uh, where does AI and where does all that fit into this conversation today? I mean, I'm, I'm interested

in, because this is a, a hot topic, I think a lot of people are wondering, like if they can trust what the machine is telling them or what the machine decides.

There's, there's obviously big debates on the, the whole spectrum of ai rather there [00:34:00] there's like the very obvious functional tool helper. Uh, augmenting people side of things. And then there's like this whole other side, which is like, what's gonna happen someday in the future if everything goes right or if everything goes wrong.

I mean, and so, and you're actually talking about some things that are going on right now with the tools that you're designing, developing, working with. Can you talk through some of that so that we can

understand kind of the state of things, but also why, uh, you're seeing the things that you're seeing when when the machine decides to sew the, the space shut for, for example.

Maria Yablonina: Um, that's an excellent question, and I think in the machine sewing the space shot, the question that I want to ask is who programmed that behavior? Um, and I am asking the same, and again, in, in the sort of on the art side of my practice, where I really like making systems that are sometimes nonsensical or [00:35:00] kind of intentionally dysfunctional.

Uh, but then in their, um, dysfunctional function, they point at something larger, be that, um, the sort of context politically or a moment in the development of technology, it's sort of like technology looking at itself and asking itself what it can do and what it cannot in the presence of the audience. Um, and I think with AI tools, to me it is really important to both acknowledge how useful they are and how immensely helpful, um, all of the new things that have been coming out, like plugins for Visual Studio where it suddenly feels like you're coding. With this assistant or collaborator looking over your shoulder. But the things in that context that really scare me are outside of the, will the machine do this or that, but rather what is the data set? Who [00:36:00] controls it? Who controls the power that comes with this machine? And can I trust that person or company or corporation? And most of the times the answer is no. I do not. And frankly, for me, every time I want to or, um, need to use, uh, any AI tool, I sort of have to think twice about what am I contributing to in terms of my data.

Um, and not because I'm worried about privacy, but I'm worried about contributing to a company that I do not trust, uh, in terms of their goals and their agendas. Um, and I would love to see that be more of a conversation where in talking about machines, we sort of shift our focus away from, it's like the machine is not the issue. A robot is not gonna take anybody's job, but a company making the robot be that a digital robot, a physical robot will in fact [00:37:00] significantly impact the labor market. Um, but looking at the machine body or the machine on the screen, I don't think is as productive as really thinking about larger infrastructural systems. Like where does the server sit? What kind of data feeds it? What are the biases inside of the data set, uh, and who benefits? That's I think, a way more important question to ask than, uh, whether or not the machine will misbehave.

Evan Troxel: think what's interesting about this though is that because the machine is a physical object versus like a a chat G P T, where you're just going

through a terminal to access this L L M output, right? That as soon as there's like a physical embodiment of that output as a thing, then that's where the psychology really plays into it and how people perceive those objects, those machines that do things that look like they [00:38:00] decided to do those things has gotta be.

A topic of conversation in the robotics industry. Can you, can you

shed some light on the kinds of conversations that are going on in around that kind of thing? Because I could imagine that there's all kinds of, again, like we keep talking about spectrums here, but there's, there's gotta be some really high level stuff that, and and what's interesting is I keep hearing experts like yourself say, we need to be having these conversations, which makes me think that we're not having these conversations so.

Maria Yablonina: Yeah, I mean, I don't, it's not, I don't think we're not having the conversations necessary, but going back to the question of interdisciplinarity, the conversations that I see in the art space or in the space of humanities and, um, like research into systems and research into, um, like the, the humanity side of, uh, social and technological systems. The conversations [00:39:00] are definitely happening there, but they do not seep through the disciplinary wall into the world where engineers are talking about how to make a robot friendlier such that people are not worried about it taking the job. 'cause in robotics, both in academia and in the industry, that is almost its own profession at this point.

Like how do we make this

embodied, intelligent device appear a certain way, such that it people trust such that people, you know,

it's kind of a. Both a design and an engineering question. Um,

Evan Troxel: It's UX for interactions, right?

Between

people

Maria Yablonina: exactly. Like even in

Madeline's work, uh, who I know you had on the podcast recently, um, the choreography of movement makes you feel about

the machine in a very different way.

And

that's why I think her work is so interesting. 'cause it really points at that boundary because it's still the same machine. The body is still the same.

Evan Troxel: right.

Maria Yablonina: Um, so yeah, I think the conversations are [00:40:00] happening, but they're siloed inside of disciplines. Um, and even inside of architecture, like there are all of these flavors, uh, of architecture within, um, like there's more of history theory, there's more design work, and then there's more technology work.

And I often find that Technology work is perceived as tech optimistic and not critical. It is often perceived as sort of still carrying the Patrick Chuma, her parametricism aesthetics or even computational design equals parametricism. It equals particular type of aesthetic.

Evan Troxel: Right.

Maria Yablonina: and that is, that is really unfortunate because I think we've moved on a long time ago.

but there's still these biases that need to be shared and conversations that need to be had because if we're, if we're not understanding and learning and gaining literacy in technology, both from the sort of technological knowhow and understanding [00:41:00] of social systems that surround technologies, what hope do we have to be

critical? And to really create impact. And I think James Bridle, talks about it in their book. The New Dark Age. Um, this question of literacy as a combination, like it's not enough to know how to code, it's not enough to know how to specialize in this one extremely niche thing. Literacy really implies understanding both high resolution and low resolution context of what technology is, what's its politics are. Again, where's the server farm and what kind of cable goes from my house and eventually ends up in the server farm. And what are the politics that surround it?

Evan Troxel: Yeah. I, that, that applies to architecture in so many ways. And I, I, I attended a online lecture with Phil Bernstein talking about somebody making a decision to put zinc panels on their project actually needs to be traced all the way down to the, [00:42:00] the slavery that's happening to make that product right.

And, and for architects just to have the literacy at some level to understand that. So when they, to understand the impacts of their decisions and, and what you're talking about, I think ties right into that. And it really, I guess the conversation isn't really about. Specialty versus generalist. It's really about literacy. I think that's a really interesting way to, to look at that because I think you could be a generalist and be very l literate, right? You can, you can understand enough about all these things to ask the right questions, understand potential impacts, know who to talk to when you need to find out more. And then there's like this, the specialist, right?

There's the, the person who just does grasshopper on, on projects for facades in this region and, and that is a very different like that. They can be very literate in that. But then how does that tie into the whole [00:43:00] building industry ecosystem? This is, this really is the call for architects over the last, decade, maybe more.

It's hard to, to say. Everybody just always needs to do more at the same time. Everybody's already drowning. And so how, how to deal with that, how to navigate that is a, is

a tough thing for sure. I, I don't just a, I don't know where, where we go from that, but it's just an interesting observation, hearing you speak about that.

I, I, I appreciate you bringing the idea of literacy to that. At least for me, it's helping me connect some dots on some things that I've been thinking about recently. It's really interesting. So, let's talk about where you're working on now. And you, you've got, you've come from this idea of the, these robots that you built that do very specific tasks and, and tell us where that has led you.

Maria Yablonina: Uh, very good question. 'cause it's leading me to a bunch of different places. I am like on one side, as an educator, I'm sort [00:44:00] of trying to figure out how to reshuffle the way we, uh, teach architects technology again, from that literacy perspective, such as comes Coupled with larger understandings of infrastructures, but also that the time spent to understanding that doesn't take away from the technical knowledge building and the technical skill building. Um, and then on the other side, uh, part of my research work is in thinking about these extremely task specific tools for construction. Um, mostly focusing on repair or interfacing with existing building systems. And then the third flavor or third side of my ongoing practice is on the art side. Um, I'm part of a artist duo with my collaborator Mitch Lama.

Um, we have a studio called maybe where we are exploring, [00:45:00] um, the way technology kind of seeps into, uh, again, the social, um, infrastructures, the way it affects us. Uh, and with our practice, we, we work with software, we work with hardware. We develop tools and devices that don't necessarily function as technology or like in a traditional way of understanding what a function is, but really function as pointers at something else. Uh, or have these functions that maybe are ridiculous or nonsensical, but create that space for thinking and untangling the complexities of what lies underneath them. so yeah, again, wearing many hats,

uh,

Evan Troxel: Yeah, I was gonna say that again,

Maria Yablonina: yeah.

Evan Troxel: 'cause that's, it comes through, it definitely comes through. There's, there's a lot going on there. I, I've, I've kind of framed it as well, you're living one life, so you're trying to live multiple lives at the same time in these different categories. Right. And, and it's like, because you [00:46:00] wanna make the most, and, and, and they're informing each other.

And that you're creating these cycles of informing information between them as you go, which makes them the flywheel that does propel itself in

some way. And I would even imagine in the, in your art endeavor that. You're creating a place where unexpected things happen that then you don't, you don't always know where you're going and you're open

to what happens to inform where you go next.

And that's a really interesting part of what art allows or enables you to do. Maybe. Maybe let's talk about that one. So what are the kinds of things that you've, that have happened in that exploration that you're pursuing?

Maria Yablonina: Um, so we're currently working on a few different projects. Uh, none of them are finished, uh, which I think is kind of symptomatic for both the way we work,

uh, and the way our attention [00:47:00] continuously expands, uh, onto new things. But, uh, I guess the current big favorite project is a collaboration between our studio, uh, the TMU University and rom, uh, the Natural History Museum, where we're looking into the idea of biome medically replicating some parts, if not whole extinct species.

So we're looking specifically into passenger pigeons, which are these species that were extremely, um, like there was huge populations, um, in North America. And then as humans started getting into agriculture, they basically went extinct because they were all hunted, uh, because it was sort of a pest,

uh, both a pest and an entertainment. Um, it was really fun hunting them because they, they, would move in these ginormous flocks. Uh, and there are all these descriptions of [00:48:00] basically like you shoot anywhere in the air and a bunch of pigeons fall down.

they were hunted to extinction there. Probably one of the more famous and kind of tragic histories of human cost extinction. Um, they went extinct in 1914, um, and today they're one of the species that, um, there's a lot of work happening in genetically. Reviving some of the extinct species and passenger pigeon is one of them, partially because of practical reasons. Um, turns out it's easier to genetically work with animals that lay eggs than it is with mammals. Uh, but also again, because there's so much history, like we know the name of the last passenger pigeon. Her name was Martha and she was at the Smithsonian and her skin is still at the Smithsonian on display. Um, so there's a lot of these layers of kind of metaphor and storytelling and narrative around them. Um, so in our work we're looking at bird skins, we're looking at bone structures, [00:49:00] we're looking at kinematic systems and we are basically trying to replicate, uh, it robotically or anima chronically. It's kind of somewhere in between. Um, but in that process of replication where again, we're not really looking for functions like flight, uh, 'cause there's plenty of people working on drones. But looking at functions like, how did this bird flap its wings during the mating, uh, rituals? And can we replicate certain choreographies and aesthetics of those behaviors? But then the whole process of doing that is, again, more of a critique of how we approach extinction, how we approach climate change, um, in this sort of alleviation of guilt. Um, so our understanding of the, the whole project of genetically reviving extinct species is like, well, you're not gonna reintroduce them into the environment. 'cause at this point they're invasive. You're not going to [00:50:00] like, it's the purpose of the Whole endeavor feels like we're doing it because we can, but at the same time, we are doing it to feel better about

having

Evan Troxel: Right.

Maria Yablonina: made it extinct.

So we kind of,

Evan Troxel: yeah. Jurassic part

going on here doing it because you can, but , but not because

we made the dinosaur extinct, but yeah. Different

Maria Yablonina: Yeah. I guess the, the elevator pitch for that project is like, we're performing techno optimism as a critique of techno optimism.

And again, as a pointer at the way we tend to use technology to sort of repair or to create these alternative narratives of like, well, things aren't too bad, we can take the carbon back out of the atmosphere. Um, but then what does that mean in terms of how we, how that changes our behavior

today? It's like, well,

if you can revive a species, then should we just stop caring?

Evan Troxel: Interesting. Interesting. Wow. Well, I, I feel like we [00:51:00] need to start wrapping up and I would love to get back to your view of kind of the practical applications. What, what is the elevator pitch to students, but also the

profession, uh, around your work? Because the experimentation and the kind of the breakthroughs that you've had, I think do have direct application.

But what, what do you say when, because it's not like people go necessarily looking for what's the latest in robotics and especially with the kind that you're working on. Um, and I'm sure sure it's. Difficult to get those stories out there and get people to pay attention to them in a world again, where everyone's already drowning in all of the things that architects are dealing with in a e c.

And so I, I'm, I would love it if you could do that here now and, and tell people why this matters. What is, what are the kinds of things that you see it actually applying to in practice, in construction, in the built environment sooner than later or now? Uh, and why, why [00:52:00] should they be interested in this and why is this important work?

Maria Yablonina: Um, well, I think from the perspective of current state of construction, again, I'm really interested in pursuing, research that focuses integration into current practices, both in terms of integration into current labor structures around tools and people on site integration into existing building stock.

So not just working with new things, but figuring out how do we actually engage with old

things like the reason So much of current building stock is demolished. Um, even things that are very technically easy to recycle like steel, it is so hard to understand what your steel building or steel structure looks like and figure out how to sort it, how to store it, what exactly are the properties that demolition ends up being the cheapest, the fastest, the easiest.

Evan Troxel: Yeah.

Maria Yablonina: Um, and I think that's exactly where there's space for these types of tools that are both kind of scalable and [00:53:00] potentially small and have, uh, potential to be fit with sensors and accompanying software systems for actually keeping track of that material and making very high resolution decisions.

So instead of demolition, maybe there is a space where again, I can show up to a building and decide exactly what parts are Need to be demolished and removed because either like the material has worn or it doesn't really work anymore, but then have enough data collected by these tools to be able to be like, no, these are fine and we're gonna keep

them. Um, and that's not necessarily the work that can be, um, done manually and if, or I don't think that's the work that can economically be done manually at a scale at which it become like, starts actually making sense

in the construction industry. So I definitely see a potential there. And again, that's where, that's the direction I'm going into with my engineering work, um, where I'm currently working on a renovation project of a building that [00:54:00] was built in the sixties and we are refitting it with a new facade system, but the building is super tall. Like it's really, really hard to both understand what the current state of the structure is. But then assuming we have understood what the state of structure is, the next layer is fitting a new system onto the old system. And basically making sure that we're installing clamps in the right spot. It's really funny that like installing a clamp ends up being a huge

problem, which doesn't sound like sexy or interesting, but it's so impactful in terms of how, again, how construction workers, uh, operate on site and where are the tasks. So the system that we're developing again, is this robot that climbs up. It knows where it is, it does some scanning, but also after the scanning is complete, it goes up and marks the point where the clamp needs to be installed, which means that the person who will eventually go up in a crane doesn't have to do complex measurement,

which means like really difficult body movements.

'cause you sort of have to

Evan Troxel: I just,

Maria Yablonina: like Yeah.

Evan Troxel: I, [00:55:00] I've li I literally, yesterday, over the long weekend,

it's like I'm standing on the top of a ladder in a very precarious position, measuring, reaching, drilling,

and it's like one small miscalculation and people are getting injured, like among, you know, equipment getting damaged.

And, and I, in the industry that we work in, it is,

I mean, there's . There's a lot of regulation going on there. There's a lot of licenses on the line. There's a lot of insurance, there's a lot of OSHA, there's all these things, right?

and it's like, I can imagine the complexities that that could potentially lead to solving for.

I mean, that that

is a, there's a lot there.

Maria Yablonina: Yeah. And I really like thinking about these tools, um, as eventually, and I mean obviously at this point it's sort of research and a lot of it is happening in the lab, but I'm really imagining them in the hands of people on site. So it's not like, and then this fancy professor showed up with her toolbox[00:56:00]

and like did a bunch of tests and then left, and nobody cares.

But really seeing them as tools, which is also why I, I don't know if that. Um, kind of came clear in the conversation, but I try to avoid the word robot lately

Evan Troxel: Hmm.

Maria Yablonina: 'cause I feel like machine is maybe a better description. Um, 'cause a machine can be a tool and a tool, and I'm not saying they're not, they're still carry all the same, like they're intelligent in a way.

They can make their own decisions in a certain way. Um, but I think the word robot again creates a certain narrative around labor while machine

and tool, um, creates a very different narrative and a very different story around who wields it. And in my perfect world, it's the construction worker who actually wields this tool rather than some sort of, um, star architect. Um, and Yeah,

Evan Troxel: And, and when you're, when you're developing this, this, doing this research, are you talking to those people? Are you involving them in that process? Because if, if it [00:57:00] truly is gonna augment them or be a, a helper to them, I would imagine they have a lot of kind of embedded job site wisdom, uh, from doing the thing over and over and what works and what doesn't.

And, and, and kind of getting a fresh approach from you combined with their intrinsic knowledge of doing that has gotta be a, a pretty magical combination.

Maria Yablonina: Yeah, at this point I'm working with a fabricator company and a research department inside the fabricator. So it's not quite, uh, we haven't yet done any onsite testing. We're planning some for later this year. Uh, but that is definitely the long-term goal. Like when these devices are actually ready to be tested, tested on site,

um, that's going to be a very important part of it. 'cause, uh, yeah, otherwise it's like developing something that is questionably useful in a silo.

Evan Troxel: right?

Maria Yablonina: so, so [00:58:00] far the interaction with onsite personnel has been conversations. It's like, do you think

this is a good idea? And they would give us some feedback. Um, but we're not quite at the stage where we're ready to actually test. Um, again, like the, the wielding is for now happening in my hands, uh, but hoping that that will get passed on to other people.

Evan Troxel: Well, and how open are they to having those conversations? Because I would imagine there is a, know, they know how dangerous it is. They know the potential bad outcomes that could happen

without tools like the ones you're talking about. So are they receptive to these ideas?

Maria Yablonina: um, it's hard to tell. Like there's obviously some discomfort around again, the automation narrative. Um, and frankly I feel a lot of discomfort with that narrative as well, which is partially why this project means so much to me, because I feel like we're not really Um, automating, like we are automating parts [00:59:00] that are extremely difficult for human, but also we're not removing the human from the loop in any way.

Again, I like to think about these things as tools rather than, um, kind of replacement technologies. Um, but also at this point we're working with very specific construction crew on a pretty high profile project, so I can't really speak to the larger industry.

Um, I don't have as much contact as I would like to.

That's against something that I'm moving in the direction of. but I'm hoping that there is space for, again, developing tools that feel like tools and developing tools that align with my values. Um, and that's where maybe the art practice comes back in. 'cause I feel like pursuing both creates a system of checks and balances where

Evan Troxel: Mm. Mm-hmm.

Maria Yablonina: putting on the artist hat. I'm like looking back at the engineering work and it's like, do I feel fully on board with this? [01:00:00] And it's like, yes I do. Okay, let's keep on going. cause again, it's so easy to fall into the shiny, uh, sort of well, isn't this beautiful? And everybody loves it and it's, um, yeah, takes a lot of work. And I guess that that brings me to the education part where that is the conversations that I like to have with my students as well. Um, understanding that so many of them will go into sort of the architecture workforce. So many of them will go into maybe research and technology or corporate technology. And as we're developing the knowledge and the know-how and the skills of how to wield technology in the design space, it is always with the underlayer of like, but what does it mean and who benefits? And can you imagine? The, the image of this technical proposal that you're painting, is that the only image that there can be? And what would be the sort of the flip narrative around that? Um,

so that to me is very important. And then on the other side, [01:01:00] I guess again, trying to figure out how to shed the Patrick Schumaher vibe and really talk about, especially in the space of computation, talk about these tools as tools, not aesthetics, not, uh, any sort of design movement or it's a tool to automate certain parts of the design process that leaves you with more time to do fun things. Um, like one of the exercises that I like to use in my, like first year introduction to, um, computational design class, like we're gonna design a grasshopper definition for you to have a staircase that is two code. but parametrically adjustable and you're gonna keep this grasshopper definition for hopefully the rest of your careers and you'll never have to draw a staircase again in your

life.

Evan Troxel: Mm-hmm. '

Maria Yablonina: cause who wants to draw staircases? Nobody

Evan Troxel: Nobody

Maria Yablonina: Um, so yeah, so thinking about those things as very [01:02:00] practical hacks as well as larger, um, kind of ecosystems of technical systems that will be more and more part of our work and more and more part of what is required from an architect.

Evan Troxel: I think one of the things that, that I keep thinking about when you're, when you're talking about engaging the construction side of it, or even the students and kind of learning, How to navigate that, but also present, uh, you know, especially in the student's case, how to think about the future engagements that they're gonna be happening and, and have some empathy for those people.

They're gonna come up with some amazing ideas, but actually bridging the gap between, uh, the innovation and the adoption of said things like you're talking about with the tools to go on the outsides of these buildings and mark the points, like scan and mark the points You're not coming at it from like, I've solved this for you.

You need to buy this thing. And we've co-developed this. It's a tool, it's a hack. It's safer. It's it, it takes the empathy [01:03:00] side into it of like understanding what they have to deal with because you've engaged them to figure that out. You've lived it in your lab as well with kinds of work that you're doing there before you go out, maybe even, and talk to them.

So there's already kind of this understanding of, look, I know what goes wrong because it's already gone wrong. Right. But I think that, that's so interesting to think about . because adoption is so hard in this industry. Like the stripes that people wear are hard earned. And so it's really hard for them to let go of the way that they've always done it and look at new ways to do it because it was so hard to get to the point that they're at.

And so there's like this, they can't let go of that because there's pride locked up in that. There's ego locked up in that. There's all of these things and they're not all negative locked up in that. And so it's, I'm glad to hear that you're talking to students also in this way of, of saying like, look, there are going, you are going to have innovative ideas in the future, but you also have to understand [01:04:00] who you're talking to and why.

And like thinking about that literacy component, bringing that back into

this part of the conversation is incredibly key because if you don't have that literacy, adoption is not gonna happen. Adoption for the ones who are literate is already really hard to get . Tools into the marketplace that literally can help save, like you said, Do you ever want to draw a staircase again? No. How many people actually have a staircase tool? Not very many. Like, they will still choose to draw the staircase every time because it's like the, it's just part of who they are. And so, I don't know. It's just, it's interesting to hear about the way that you're tying this back into the educational component, tying it into the research and the art component and the practical component.

And, and I, it's, it's great to hear kind of this, like you said, you're living, you're wearing many hats. You're living many lives at the same time. But I do think that that is kind of, I dunno if it's fortunate or unfortunate, like that's kind of just what you have to do, like [01:05:00] to, to make progress in, in all of these things at the same time.

And

Advance down the field. I mean, because if you don't, and you were just in the silo and you just come to somebody with the prescribed solution, it's, it's likely not gonna get any, uh, attraction at all.

Maria Yablonina: Yeah. And, and it's a great privilege, frankly, to be able to be in that space where, you know, multi hat wearing is a thing. And

Evan Troxel: Hmm.

Maria Yablonina: I learned so much from, again, entering these different worlds every time. Like, I don't know, attending a more sort of corporate conference where most things aren't very interesting or don't necessarily align with my values, but then also using that opportunity as almost a tool for diagnosis.

Evan Troxel: Hmm.

Maria Yablonina: And then bringing it back into my practice or vice versa, being in a space where things and structures that I haven't thought about, um, in terms of like layers of metaphor, layers [01:06:00] of politics. And it's like, oh my God, I have to now take that and bring it back to the other space to make sure that I

kind of, again, evaluate, uh, from this new perspective. And it's such a huge privilege, um, and kind of honor to be able to be in those, be invited and sort of be welcomed. Um, and I think in a way that comes with the academic position, I feel like in the industry that might be harder. but I would love to see more of that crossing of disciplinary boundaries,

both in academia and in industry. And I don't quite know what needs to happen for that to properly happen. Uh, I have this sort of term that I often use the. It's interdisciplinary washing where everything is labeled as interdisciplinary, but in reality it's just like a couple of silos coming together, uh, temporarily. Um, but yeah, I'm really hopeful that that's gonna be the case more and more where we really come to, know, the table with a [01:07:00] blank sheet of paper and decide together what needs to be done rather than, I dunno, an architect approaching a software engineer being like, these are the tasks, do them for me.

Or the other way around,

uh, a CS person approaching an architect being like, I have this design tool, now use it. I think those types of collaboration don't work and we really need to figure out how to combine the value systems translate between languages and sort of ideate together rather than outsource tasks.

Evan Troxel: Well, you said when you started off I have, I was trained as an architect

and you said that's kind of a theme. And to me that is kind of the hope that I see. The thread that runs between the people who come on this show to talk about this stuff is like you have quote unquote left architecture, but you haven't left the love for

transformation. I mean, it, it is an evolution of the practice. It is an evolution of

the industry and to[01:08:00]

to

Maria Yablonina: a professor at an architecture faculty.

Evan Troxel: Yeah. Right. And you're, and you're solving, I mean, the, the, what I say is I say, you know, you instead of working in the profession, you, you help work on the

profession and

like zooming out and saying like, like looking at it as the puzzle that it is, because I think there's so many pieces.

That only are concerned about them, and that's fine. A lot of times that's all you can do. And maybe, maybe you think about the pieces that are adjacent to you, but zooming out and looking at it at this very large scale of the whole puzzle is kind of a rare thing. But I think it is a thread that I do see with people who come on the show to talk about the thing that they're doing and why they're doing it.

And so I, I, you're, you're perfectly aligned with, with all that. And so to hear these different categories and, and endeavors that you're pursuing, it totally makes sense when, when you talk about it, I don't think it would make sense on paper, right? Because it's like,

no, there's no, way somebody can do all [01:09:00] of these things and do them all well.

But I think you are embodying that in a, in an amazing way. So thank you.

Maria Yablonina: Thank you so much. That means a lot.

Evan Troxel: And thanks for coming on the show today. I, I am gonna have links to everything that you are doing in the show notes. And, uh, again, it was a pleasure to have this conversation and I, I look forward to hopefully doing it again sometime,

Maria Yablonina: Thank you so much for having me. It was really nice to share all the hats and all of the anxieties that come with the hats. Really appreciate it.

Evan Troxel: Yeah, it can't be easy. I, can appreciate that. So you Maria.

Maria Yablonina: Thank you.